Recommended Voluntary Forest Management Practices for New Hampshire

6.10 WOODLAND RAPTOR NEST SITES

BACKGROUND

Suitable nest sites are limited for woodland-nesting raptors. These birds can be sensitive to human disturbance and habitat changes in the vicinity of nests. Continued existence of these birds depends on an adequate supply of potential nest trees.

Accipiters (sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks, and northern goshawk) build large stick nests on large branch fans of white pines next to the tree bole, and in multipronged “basket” forks (where three or more large branches meet) of mature hardwoods at different canopy heights. They often reuse the same nest in successive years, or build a new nest in another nearby tree. Goshawks build nests in the base of the canopy often in areas with prior goshawk nesting. Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks tend to build their nests higher in the canopy. Sharp-shinned hawks tend to nest in younger, dense forest stands; Cooper’s hawks nest in more open forests. Goshawks nest in more mature forests in or near large white pines.

Buteos such as red-tailed, red-shouldered, and broad-winged hawks build large stick nests in “basket” forks of mature hardwoods and on large branch fans of white pines that are often near the edges of open, nonforest areas such as upland openings, marshes, beaver ponds and old woods roads. Red-shouldered hawks nest in mature woodlands near water or wetlands.

Ospreys nest on dead or dead-topped trees, most often in white pines but occasionally in other tall softwoods. Osprey often nest near large lakes, wetlands or stream riparian zones, but may occasionally nest in upland settings some distance from open water.

Bald eagles usually nest within half a mile of water along shorelines of large lakes and estuaries in large white pines or hardwoods. Both osprey and bald eagle nests are typically used for years or even decades, with pairs adding new nesting material each year.

Cavity-nesting owls (barred, long-eared, saw-whet, and screech) use a range of sizes of cavity trees in forested and riparian areas. Great horned owls commonly occupy large stick nests built by red-tailed hawks, crows, ravens, herons, and squirrels. Barred and long-eared owls may also use stick nests.

Excessive human activity near raptor nests in the early weeks of the breeding season may cause a pair to abandon the site; or if later in the nesting cycle, may cause an incubating or brooding female to flush from the nest, leaving eggs or nestlings vulnerable to fatal chilling or predation.

OBJECTIVE

Manage for suitable nest trees and potential replacement nest trees for woodland-nesting raptors and avoid disturbance of nesting pairs during the breeding season.

CONSIDERATIONS

- Cooper’s hawk, northern goshawk and red-shouldered hawks are New Hampshire species of greatest conservation need.

- The number of nesting pairs of ospreys statewide has steadily increased to 68 in 2008 from the early 1980s, when 10 to 20 pairs nested in Coos County near the Androscoggin River. Though ospreys were removed from the state-threatened list in 2008, they remain a New Hampshire species of greatest conservation need.

- The number of bald eagle nesting pairs steadily increased to 15 in 2008 since bald eagles resumed nesting in New Hampshire in 1988. Bald eagles were removed from the federally threatened list in 2007 and remain on the state-threatened list and as a species of greatest conservation need.

- No regional surveys assess the status of owls.

- Identifying woodland raptor nests can be difficult without the birds’ presence and activity. Active nests can be difficult to determine outside of the nesting season (mid-February through the end of July). Multiple raptor nests indicate areas where past raptor nesting has occurred. Active nest trees are often discovered during harvesting.

- Because of their poor form (from a timber-value perspective), potential raptor nest trees may be removed during timber stand improvement.

- While northern goshawks will aggressively defend their nest sites, some raptor species such as red-tailed and broad-winged hawks can tolerate nest disturbances better than other species.

- Nesting raptors may tolerate vehicular traffic on regularly used roads. However, all-terrain vehicle (ATV) traffic on otherwise unused roads and trails can be a disturbance factor.

- Great horned owls prey on both adult and nestling hawks and can discourage some hawk nesting attempts in landscapes with a significant open, nonforest component.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- Look for stick nests in sawtimber-size white pine and hardwoods along woods roads and trails, near water and forest openings.

- Avoid recreational use of logging roads adjacent to active nests during the raptor nesting season (mid-February through the end of July). Trails may be temporarily rerouted around nesting areas.

- Retain trees containing large stick nests and some potential nest trees, especially those hardwoods with multipronged "basket" forks, and large cavity trees (6.2 Cavity Trees, Dens and Snags).

- In clearcuts, leave a group of several large trees for each 5 to 10 acres to ensure future availability of mature trees for nest sites. These clumps also can serve cavity-nesters' needs.

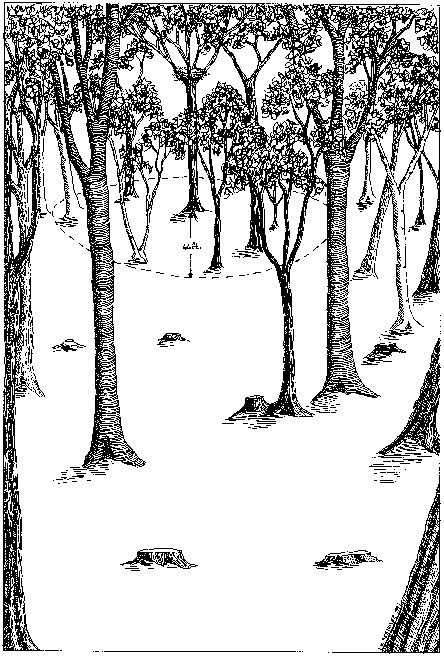

- Where raptor nests are found, leave a partially closed canopy using either single tree management or a small uncut buffer of at least a chain (66 feet) around the nest trees, leaving more than just the nest tree(s).

- Minimize nesting-season disturbances around active nests.

- Temporarily limit forest management activities (tree cutting, road construction, etc.) within 10 chains (660 feet) of active raptor nests during mid-February through the end of July; with the understanding that tolerance levels are highly variable among raptor species and individuals of a given species and that each situation can be different.

- If nests are discovered during harvesting, continue working in another area, if possible, while the birds are nesting and until the young raptors have fledged.

- For bald eagles, avoid human activity within 5 chains (330 feet) of active nests from February 1 to August 31. Contact the Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program at N.H. Fish and Game for assistance when planning a harvest within one-quarter mile of a nest. Refer to timber operations and forestry-practices guidelines in National Bald Eagle Management Guidelines.

- Though peregrine falcons aren't tree-nesters, minimize potential recreational and rock-climbing disturbance around cliff-nesting sites during the breeding season.

CROSS REFERENCES

2.2 Forest Structure; 4.2 Wetlands; 4.3 Forest Management in Riparian Areas; 6.2 Cavity Trees, Dens and Snags; 6.13 Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Elliott, C.A. 1988. A Forester's Guide to Managing Wildlife Habitats in Maine. University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Orono, Maine.

USDI Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. National bald eagle management guidelines. http://www.fws.gov/pacific/eagle/NationalBaldEagleManagementGuidelines.pdf Accessed February 23, 2010.