Recommended Voluntary Forest Management Practices for New Hampshire

7.2 SEEPS

BACKGROUND

Seeps are small, critical habitats only detected through site visits.

Seeps or seepage wetlands are springs, pools, or other wet places where groundwater naturally comes to the surface. Soils in seeps remain saturated for all or part of the growing season and often stay wet all winter. Surface waters often percolate back into the ground through porous layers of sand or gravel, but on hillsides, seeps may be headwaters for small streams.

There are five broad categories of seep communities: (1) seepage marsh (2) riverside seep (3) seepage swamp (4) seepage forest and (5) forest seeps.

(1) Seepage marshes occur in association with wetland borders, in headwaters, and along stream drainages.

(2) Riverside seeps occur along larger rivers with outcrops, open bedrock, cobble, sand, or silt substrates.

(3) Circumneutral (i.e., having water around neutral pH) seepage swamps are rare features of coastal lowlands characterized by red maple, black ash, and swamp saxifrage.

(4) Northern white cedar seepage forests and northern hardwood seepage forests (characteristic trees include sugar maple, yellow birch, and balsam fir) occur in northern New Hampshire.

(5) Forest seeps occur throughout the state in stream headwaters, on hillside slopes, along swamp margins, and on steep faces of river terraces. Trees are similar to the surrounding forest, and herbaceous vegetation is abundant, diverse, and variable. Acidic Sphagnum forest seeps area notable type, most frequent in red spruce, black spruce, and balsam fir forests at higher elevations in the White Mountains and further north.

Trees aren't a significant part of seepage marshes and riverside seeps. Seepage swamps, seepage forests, and forest seeps are typically small (less than or equal to 1/10-acre) inclusions within upland forests, isolated from larger wetlands. Seepage swamps and forests occur over bedrock or till, on seasonally saturated sloping transitions between uplands and flat swamps, and on lower mountain slopes.

Seep waters may remain underground for many years, producing clean waters and warmer temperatures than typical surface waters in winter and cooler-than-typical surface waters in summer. Seep habitats are important for animals and plants because their flow may keep the water from freezing during winter and they are the first to green up in the spring. Black bear prefer seeps as important food sources in the spring and summer. Deer and moose seek seeps for food, water, and occasionally elements like calcium or sodium that may be present in the groundwater.

Seep waters may remain underground for many years, producing clean waters and warmer temperatures than typical surface waters in winter and cooler-than-typical surface waters in summer. Seep habitats are important for animals and plants because their flow may keep the water from freezing during winter and they are the first to green up in the spring. Black bear prefer seeps as important food sources in the spring and summer. Deer and moose seek seeps for food, water, and occasionally elements like calcium or sodium that may be present in the groundwater.

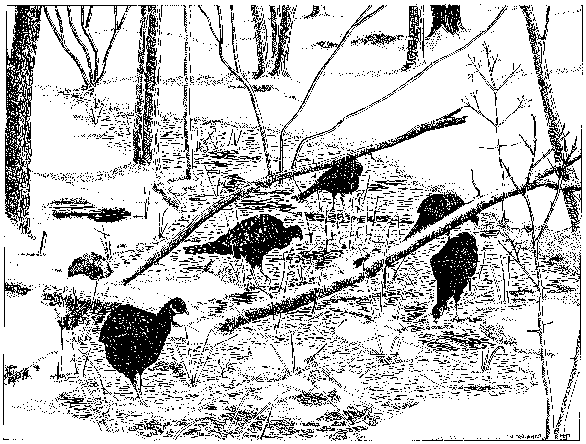

Northern dusky and two-lined salamanders prefer seep habitats, and they in turn attract predators such as skunk, raccoon, and river otter. Woodcock and robins depend on seeps for water and food (e.g., earthworms, insect larvae) after migrating and as a refuge after early spring snowstorms. Ruffed and spruce grouse are attracted to seeps for water during the winter and fresh plant food in the spring. Wild turkeys favor seeps in winter.

Seeps located adjacent to streams or rivers maintain coldwater habitats for trout and salmon during summer months when warmer water can result in fish mortality. These same sites also foster fish survival in the winter by creating a warmer environment than would normally occur. Trout and salmon abundance is related to seeps and groundwater upwelling in streams and rivers.

Several rare plants are associated with seeps. For example, calcareous riverside seeps provide habitat for six rare plants including the endangered Garber's sedge, hair-like beak-rush, and muskflower. Acidic Sphagnum forest seeps and circumneutral hardwood forest seeps are particularly rich in rare plants.

OBJECTIVE

Avoid direct impacts to seeps and minimize disturbance to the adjacent forest during timber harvesting.

CONSIDERATIONS

- Some seeps meet the statutory definition of wetland and are subject to state wetlands regulations.

- The N.H. Natural Heritage Bureau can help when planning forestry activities near seeps to avoid or minimize impacts to rare plants and exemplary natural communities.

- Removing surface soils by road construction or other activities may inadvertently create seeps that then become subject to regulation by the N.H. Dept. of Environmental Services.

- Harvesting near seeps may alter the natural community.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- Delineate seeps before harvesting.

- Maintain a vegetated buffer around seeps to prevent sedimentation, increased water temperature, and increased drying from reduced shading.

- Locate roads and skid trails in the spring or summer when seeps are most visible.

- Conduct selection harvesting or uneven-aged management near seeps when the ground is frozen.

- Keep tree tops and slash out of seeps and wildlife trails that access seeps.

- Minimize the interruption of groundwater flow by adhering to best management practices (BMPs).

CROSS REFERENCES

4.2 Wetlands; 4.3 Forest Management in Riparian Areas; 7.1 Natural Communities and Protected Plants; 7.6 High-Elevation Forests; 7.7 Steep Slopes.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

N.H. Dept. of Resources and Economic Development, Division of Forests and Lands. 2004. Best Management Practices for Erosion Control on Timber Harvesting Operations in New Hampshire. State of New Hampshire. http://extension.unh.edu/resources/files/Resource000247_Rep266.pdf Accessed March 13, 2010.

Sperduto, D.D., and W.F. Nichols. 2004. Natural Communities of New Hampshire. N.H. Natural Heritage Bureau, Dept. of Resources and Economic Development, Concord, N.H. 229 p.

Taylor, J., T.D. Lee, and L.F. McCarthy (eds). 1996. New Hampshire's Living Legacy: The Biodiversity of the Granite State. N.H. Fish and Game Dept. Non-Game and Endangered Wildlife Program, Concord, N.H. 98 p.