Reactive vs. Proactive Forest Management

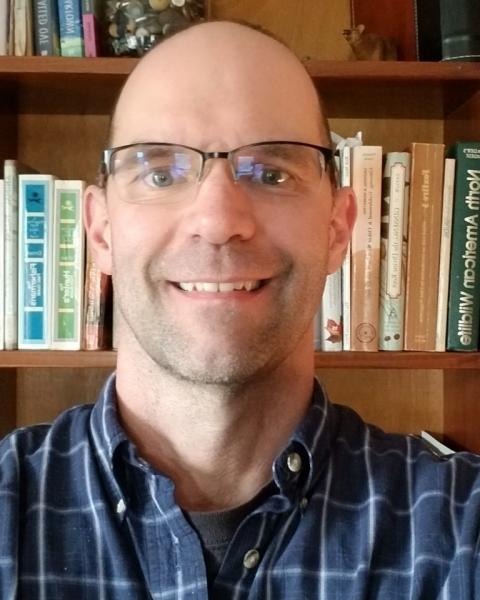

Above Photo: Unhealthy crowns on pine trees as a result of a combination of root rot and needle cast.

In the course of walking and observing many acres of forest land, I often see what I like to call “reactive management”. As the name implies, it is management that takes place as a reaction to some event – a windstorm, an insect outbreak, an invasive plant infestation, or simply an overcrowded forest that has begun to show signs of excessive mortality.

A Dynamic Ecosystem

Many people like their woods the way they are and don’t want them to change. This is understandable – a parcel of woods can be a peaceful, seemingly permanent place; and change can be hard. Forests, however, are dynamic ecosystems that are continually changing. The changes are often subtle, invisible to us on a day-to-day or even year-to-year basis. Other times the forest changes drastically, as when a microburst blows down a lot of trees, or an ice storm damages thousands of acres.

Foresters talk to landowners about managing their forests to meet their goals – thinning to improve health and vigor, to increase growth of timber or production of seeds; or to harvest mature trees to encourage regeneration and to create dense cover for wildlife. But these activities often involve felling trees, and usually extracting the trees from the woods to be used as products. This man-made disturbance can look messy, and can be disruptive to the peace and tranquility of the woods. And peace and tranquility, after all, are one of the main reasons that many people own woodlands in the first place. Their reluctance to disturb the forest is understandable. The disruption, however, is temporary, and carefully planned and implemented harvesting can lead to a forest that meets the landowner’s goals.

Managing the Forest to Meet Goals

There’s nothing wrong with letting a forest develop on its own, and allowing natural processes to take their course. Natural processes, however, don’t follow a set pattern, nor do they necessarily lead to a desirable forest. This is especially the case with all of the stressors that our modern forests face: invasive insects and plants, diseases, past clearing for agriculture, logging, hurricanes, ice storms, and more. Despite all these disturbances and changes, forests persist and continue to grow. Allowing “nature to take its course” is one option. However, a landowner may not get the forest that they want, one that meets their goals for wildlife habitat diversity, valuable timber, views, or recreational trails.

Harvesting trees, when done with sound forestry practices and the landowner’s goals in mind, is a valuable and useful tool for shaping the forest to achieve those goals. Without this tool, the outcome is up to the vagaries of nature.

A good example is a forest I visited recently. It was named for the large pines growing there. No cutting had been done for many decades, because people did not want to disturb or change the forest. Unfortunately, root rot set in, and, exacerbated by a fungal disease in the needles, many of the tree crowns are in poor condition. Most of the pines are dead or dying, and shade tolerant hardwoods have been developing in the understory for years. A salvage harvest was conducted in response to the pine decline. Many trees were not salvageable because they were dead, the wood unusable. The decline of the pines and the subsequent harvest created a drastic change in the forest’s appearance. There are few young pines because of the shade cast by the canopy; shade tolerant hardwoods are taking over. It is still a functioning ecosystem; it’s simply not the forest of majestic pines that it once was. The harvest is a great example of “reactive” management. Proactive management, on the other hand, designed to perpetuate white pine, would have resulted in a continuing pine forest.

Proactive Management

Instead of reacting to an event or condition, proactive management anticipates changes that will take place, and works with the soils, site characteristics, and forest vegetation on site to accomplish the landowner’s goals. In the pine stand, some harvesting during a good seed year that opened up the canopy and exposed mineral soil sufficiently to allow pine to regenerate, would have started the next generation of pines to replace the old ones. The forest would have retained a significant portion of pines.

Another example of reactive management vs. proactive management is when a landowner is interested in generating timber income. Stands left alone over the years tend to be overcrowded. The trees thin themselves out to an extent through mortality, but the ones that survive may not be the best quality. The owner decides to harvest some trees to generate some income, and is disappointed to find that most of the trees are low value pulpwood, firewood, or chips. The much more valuable sawlogs are few, because no proactive management was ever done to increase the amount of sawlogs in the stand. It’s akin to planting a garden, then never thinning or weeding it, and expecting a nice yield of quality vegetables at the end of the season. Forests are the same way – making little to no investment yields a poor return. In the case of a forest, it takes decades to see the results of action, so it’s important to be proactive and start management sooner than later.

It's about Goals

It comes down to what the landowner is trying to accomplish on their land. If there are specific goals in mind, whether wildlife, timber, aesthetics, or a combination thereof, chances are that management will be needed to accomplish those goals.

Given the human-dominated landscape we live in, managing forests to provide for a diversity of wildlife habitats and the sustainable growth and harvest of timber provides many benefits; benefits that forests left to follow natural processes don’t automatically provide.