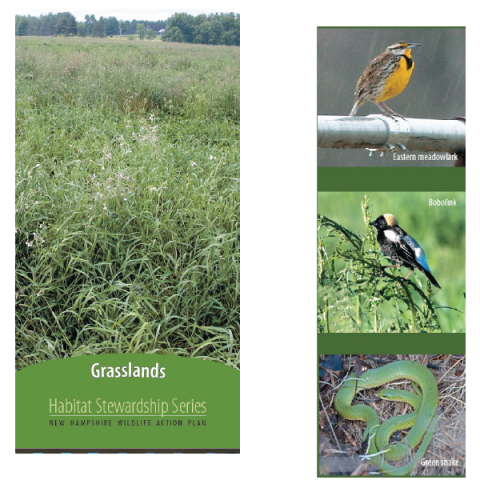

Grassland habitats are an increasingly rare site in New Hampshire. More than 70 species of wildlife use these open areas of fields and wildflowers to meet their needs for food, cover, or breeding. Most of today's grasslands are the result of land clearing, and require maintenance. If left alone, these habitats will grow back into shrubs and small trees, reverting eventually to forest. Learn to recognize the habitat value of grasslands and discover what you can do to maintain and conserve these special habitats.

Vegetation growing in grassland habitats may be tall (over four feet), short (less than 6 inches), or a combination. Vegetation height plays an important role in determining which wildlife species will use the habitat. A common trait of all grassland habitats is that they contain few (if any) trees or shrubs.

Today, most plants growing in grasslands are non-native grasses, introduced by humans for agriculturaluses. These include timothy, Kentucky bluegrass, orchard grass and perennial ryegrass. Two native grasses, big bluestem and little bluestem, as well as native wildflowers such as goldenrod and aster, are also common in our grasslands today.

Types of Grassland Habitats in New Hampshire

Agricultural Fields

The most common grassland habitats in New Hampshire are agricultural fields such as hayfields, pastures, and fallow fields. Here, vegetation consists of a mixture of grass species, or a combination of grasses, sedges, and wildflowers.

Other Grasslands

Airports, capped landfills, military installations, and wet meadows may also function as grassland wildlife habitat if they support similar vegetation. Croplands are also used by many grassland wildlife species, and are also important as potential grasslands, since they may be easily converted to grow grass if crop farming practices are abandoned.

Historical Changes in Grassland Habitats

Historically, Native Americans and beavers were the primary forces responsible for creating and maintaining grassland habitats in New England. Native Americans created grasslands when they burned the land for agriculture and to improve forage for game species such as white-tailed deer. At the same time, ponds above abandoned beaver dams grew into grassy meadows after the water drained and the nutrient-rich soil was exposed to sunlight.

In more recent history, fire suppression and limits to where beavers are allowed to build dams has meant that grasslands are restricted mainly to agricultural areas. The peak of agricultural clearing in the state occurred in the mid-1800s. Since then, New England has been losing grassland habitats, which have grown back into forest. With their well-drained soils, tree-less fields, and ample road frontage, agricultural lands also offer attractive sites for development.

Today most grasslands in New Hampshire require maintenance by humans. If left alone, these habitats will grow back into shrubs and small trees, reverting eventually to forest.

Where are New Hampshire's Grasslands?

Development and natural forest succession have combined to reduce grassland habitats in New Hampshire to the point that grasslands currently cover only about four percent of our landscape. However, large grassland habitats (those greater than 25 acres in size) still exist in every county in New Hampshire, with the highest concentrations in Grafton County (with 20 percent of our remaining grasslands), Merrimack County (13 percent), and Coos County (12 percent). Some level of conservation restriction protects about eight percent of New Hampshire’s large grassland habitats.

The map at right was created using NH Wildlife Action Plan mapping data. To learn more, click here.

Climate Vulnerabilities for Grasslands

- In general these habitats are currently believed resistant to climate change as long as management continues.

- Increased diversity and abundance of invasives (particularly plants).

- Potential for loss of wildlife value to these habitats from intensified management resulting from a longer growing season and an increased demand for biomass fuels.

Click here for the Early Successional Climate Assessment, a section of the Ecosystems and Wildlife Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2013), an Amendment to the NH Wildlife Action Plan

Agricultural Practices & Bird Nesting

Without the work of farmers and other landowners, most grasslands would quickly revert to forest. However, the timing of mowing can affect a field’s ability to provide habitat for grassland-nesting birds and other wildlife. Farmers growing high-quality forage for livestock usually mow their fields two or three times during the summer. At least one of these mowings typically occurs between May and mid-July, a time that corresponds with the nesting season for most grassland-nesting birds. Mowing during this period can destroy nests and eggs, kill fledglings, or cause adult birds to abandon their nests.

Grassland-Nesting Birds

Bird species that depend on grasslands have declined, along with their habitats, faster than any other group of birds in New England. Most grassland-nesting birds are “area sensitive,” which means they won’t nest in fields smaller than a certain size. Click on the bird name to go to the NH Wildlife Action Plan profiled for that species, if available.

| Grassland Bird Species | Required Minimum Field Size | Preferred Vegetation Height in Fields |

| Bobolink | 5+ Acres | Dense grass taller than 3 feet |

| Eastern meadowlark | 15+ Acres | Dense grass and wildflowers taller than 3 feet |

| Savannah sparrow | 20+ Acres | Prefers sites with short and tall vegetation |

| Grashopper sparrow | 30+ Acres | Prefers sites with short, sparse grass, listed as a state-threatened species |

| Northern harrier | 30+ Acres | Forages in short grass fields, nests in wet meadows, state-endangered species |

| Upland sandpiper | 150+ Acres | Prefers sites with short, spare grass; very rare, state-endangered species |

Wildlife Found in Grasslands

Grasslands of all sizes ares used by over 150 different wildlife species throughout the year. Below are some examples of species that depend on grassland habitats. Be on the lookout for these species, and follow the stewardship guidelines provided to help maintain or enhance grassland habitats in your area. Species of conservation concern—those wildlife species identified in the Wildlife Action Plan as having the greatest need of conservation—link to their Wildlife Action Plan profile:American bitternGrasshopper sparrow*Smooth green snakeAmerican kestrelHorned larkTurkeyBlack racer*Northern harrier**Upland sandpiper*Blanding's turtle**Northern leopard frogVesper sparrowBobolinkPurple martinWhip-poor-willEastern hognose snake**Savannah sparrowWhite-tailed deerEastern meadowlarkSmall rodentsWood turtle

* state-threatened species

**state-endangered species

Stewardship Guidelines for Grasslands

- Grasslands of any size provide valuable habitat for wildlife in New Hampshire. If you own fields, maintain them by mowing in the fall at least once every three years to discourage trees and shrubs. It is much more difficult and expensive to create a new field than to maintain an existing field by mowing.

- Focus land conservation on large grasslands (greater than 25 acres in size), which benefit the greatest number of wildlife species and are increasingly rare in the state.

- Where possible, remove all shrubs and trees growing in the middle of fields, as these decrease the useable acreage as perceived by grassland-nesting birds.

- In fields where intensive agricultural production is not an issue, mow fields after August 1st, the end of grassland-breeding bird season. Mowing even later (August-October) is ideal, since this allows late-flowering wildflowers such as aster and goldenrod to provide nectar for migrating butterflies. Areas where later mowing may be possible include airfields, capped landfills, fallow fields, edge habitats, marginal farmland, weedy areas, and fields producing bedding straw

- In agricultural fields, modifications to mowing techniques can help reduce impacts on grassland-breeding birds during the breeding season (May through mid-July):

- Raise mowing bar to six inches or more in areas with grassland bird concentrations.

- Grassland birds roost in the fields at night, so avoid mowing after dark.

- Use flushing bars on haying equipment (for more information, contact the Wildlife Division of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department at 271-2461).- Delay mowing in wetter areas or in grasslands along rivers - Farmers are faced with many pressures during the growing season—variable weather, equipment demands, planting schedules—making it difficult for them to incorporate a refined mowing technique and schedule to accommodate grassland-nesting birds. However, interested farmers have a number of federal and state cost-share programs available to help pay for practices that benefit wildlife. Contact your county UNH Cooperative Extension office or the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for more information about these cost-share programs

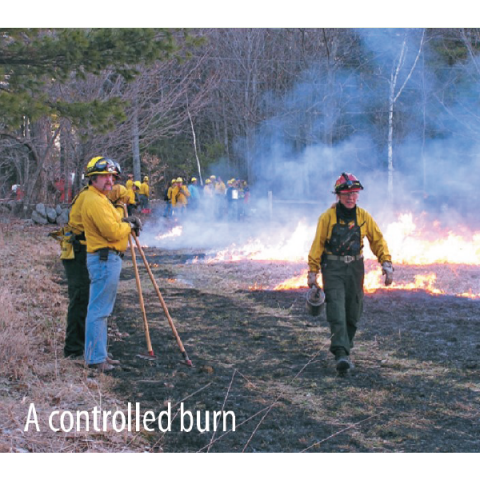

- Burning fields, particularly in areas with poor soil, can improve soil nutrients and mimic historical disturbances to grassland habitats. Burning will also help spread native grasses (see below) if they already exist in a field. Some New Hampshire landowners have established partnerships with their local fire departments to burn fields on an annual basis as training for firefighters.

- Warm-season grasses, many of which are native to the U.S., may be a viable alternative to (non-native) cool-season grasses as an agricultural hay crop. Warm-season grasses are more difficult to establish, but they offer some benefits to landowners willing to take on the challenge. They require less fertilizer, lime, and herbicides, and are more drought-tolerant. For wildlife, they offer better nesting cover (growing as in bunches, with space between for movement and nests), a more dependable food source, and better winter cover, since they don’t mat down during heavy snows. The NRCS and UNH Cooperative Extension can provide advice and possible cost-share funds to plant warm-season grasses.

Managing Small Fields for Wildlife

Many landowners own fields smaller than five acres. These fields are still important for other wildlife species, and as foraging areas for grassland birds nesting in nearby larger fields or migrating songbirds passing through. Landowners can manage their fields to improve the overall plant and wildlife diversity by:

- Mowing fields only once every two or three years to increase wildflower and insect diversity.

- Mowing as late in the fall as possible (September-October) to allow late-blooming wildflowers to form and provide nectar sources for migrating butterflies.

- Maintaining some areas of bare ground (poor soils or heavily-grazed areas) for such species as killdeer and horned larks.

- Establishing a rotational mowing or grazing program in which different parts of a field are mowed/grazed at different times. This creates a patchwork of different grass heights that provides cover and feeding opportunities to the greatest number of wildlife. Contact your county UNH Cooperative Extension Agricultural Educator for more information on establishing a rotational mowing or grazing program on your land.

Additional Resources - Grassland Habitat Management

Habitat profile for grasslands from the NH Wildlife Action Plan - includes information about the condition and location of this habitat, the threats facing this habitat, and conservation actions recommended by biologists to protect grassland habitats in New Hampshire.

- NH Wildlife Action Plan - click here to link to complete information about species and habitats of conservation concern in NH (links to NH Fish & Game website)

- Managing Grasslands, Shrublands, and Young Forest Habitats for Wildlife: A Guide for the Northeast - an in-depth, technical guide to managing open areas for wildlife, published by NH Fish & Game.

- Massachusetts Audubon Website on Grassland Birds - an excellent website on grassland bird conservation and habitat management for New England

- Univerisity of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension publishes a guide on how to manage for grassland birds using rotational grazing.

Photo Credits on this page: Matt Tarr; Malin Ely Clyde; Brett Calverley, Ducks Unlimited Canada; Debbie Stahre (webofnature.com)

Research for this webpage and accompanying Habitat Stewardship brochures was conducted by UNH Cooperative Extension staff with support from the Sustainable Forestry Initiative and NH Fish & Game.

Photo Credits on this page: Matt Tarr; Malin Ely Clyde; Brett Calverley, Ducks Unlimited Canada; Debbie Stahre (webofnature.com)