Beyond the Buzz

There's lots of talk these days about pollinator gardens as the awareness about bee and pollinator decline grows. Yet many are taking up the call without giving much thought to what it takes to successfully support pollinators. Does seeing lots of bees on lilacs and lavender in our gardens, for example, mean that pollinators are flourishing?

“Not necessarily,” according to UMass Dartmouth researcher, Robert Gegear. Gegear has studied this topic in great depth by examining the foraging behavior of bumblebees. His fascinating citizen science project called “Beecology''* was instrumental in gathering data for this work. Gegear’s startling message is, “We can’t look at the numbers of bees and other pollinators and assume everything is ok. Because it is not!”

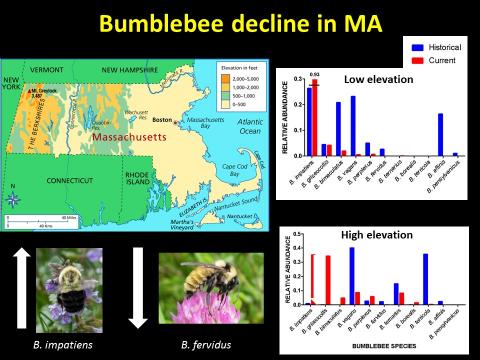

“Most of the bees you see right now are Bombus impatiens, the common eastern bumblebee,” says Gegear. “People see a lot of these bees and it gives them a false sense of security.”

The problem is that this abundance of bumblebees involves only a single species--not a diversity of species, according to Gegear. He points out that as recently as 2015 there were eleven species of bumblebees in Massachusetts. Now there are nine and three of these could easily disappear in the next decade unless we act now.

Bumblebee studies in NH show a similar trend. UNH researcher Sandra Rehan documented the increasing numbers of B. impatiens statewide while noting declines in the same species that Gegear lists. In addition, the Rehan team completed a native bee study in 2019 showing that 14 non-bumblebee species are equally at-risk in NH.

Gegear makes a clear distinction between native wild bees that play a critical ecological role and bees of agricultural importance like the managed non-native honeybee. In agriculture, bee abundance is the only consideration. Yet only 5% of the thousands of native bee species can feed on agricultural crops. Because many of the non-agricultural bees that contribute to overall ecosystem health are in trouble, Gegear urges shifting our focus to them.

Bombus terricola is an at-risk species likely found in NH.

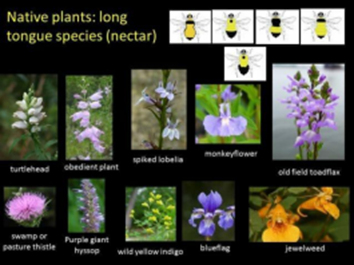

Gegear explains that certain hereditary structural characteristics such as bee tongue length and flower shape influence bumblebee feeding behavior and whether it can feed on a given plant. Such characteristics have resulted from eons of co-evolution between pollinators and local native plants. Interestingly, Gegear found that bumblebees having longer tongues are some of the species at greatest risk because the tubular-shaped flowers that they rely on have declined.

In contrast, exotic non-native plants (e.g. butterfly bush and cosmos) do not share a co-evolutionary history with local native bees. Yet B. impatiens thrives in great numbers on these non-natives, allowing it to outcompete and push out the at-risk bumblebees. Thus, a pollinator garden made up entirely of non-native flowers will destabilize the plant-pollinator community and can do more harm than good in terms of bee conservation and overall biodiversity.

Another well-known researcher, Doug Tallamy, focuses a wide lens on the complex relationship between plants and all kinds of insect species. Tallamy claims that increased propagation of “alien plants” (non-natives) is a major factor in the die-off of many of the insect species that birds and wildlife depend upon. His best-selling book, Nature’s Best Hope, has energized a movement of homeowners dedicated to rebuilding biodiverse backyard landscapes through a project called Homegrown National Park.

Gegear encourages gardeners to consider their objectives. He says, “If your goal is a showy ornamental garden, then great! Go for it!” But if conservation is the goal, rethinking what we put in our gardens is key. Like Tallamy, Gegear promotes propagating native flowers to reestablish what he calls “wild pollination systems.” Planting natives will have a “cascading positive effect on many other species” and is crucial to protect biodiversity. Even though there is no immediate agricultural or economic incentive for well-maintained native plant-pollinator systems, the long-term benefits to ecosystem and human health are immeasurable.

The exciting news is that both Tallamy and Gegear report that restoring critical habitat by planting natives works! Gegear confirms that “almost immediately, as soon as the plants start to bloom, the at-risk bee species start to show up.”

Gegear offers ideas for how to recreate critical habitat. He suggests starting with an inventory of the plants in your garden. List each plant noting whether it is native (to the local area) or invasive. The Native Plant Trust Go Botany website is useful for determining native status.

Next, Gegear recommends removing invasive plants. That means that plants on the New Hampshire Prohibited Invasive Plants List like burning bush, non-native honeysuckle, barberry, autumn olive and privet must go. Gegear includes butterfly bush because it is an aggressive exotic that attracts loads of common bees but is detrimental to overall pollination system health. Though Massachusetts and New Hampshire don’t list it as prohibited, other states are beginning to.

Gegear recommends starting off with one appealing, high-impact native plant such as a Carolina or Virginia rose which will support a broad range of pollinators including those at risk.

Next, consider planting a native willow. Early blooming trees like native willow and eastern redbud are critical because they provide sustenance to threatened pollinators when other food is scarce. In fact, a good number of the at-risk wild bees identified in the 2019 NH study including early mining bee species depend on these trees that bloom in late winter.

For those wanting to do more, Gegear compiled a detailed native plant list to target at-risk bumblebees, especially those with long tongues, as well as other threatened pollinators. The goal is to select a variety of native flowers, including tubular-shaped species, that bloom throughout the growing season. Possibilities include flowering raspberry, meadowsweet, jewelweed, giant purple hyssop, prunella, obedient plant, several penstemons, and more. (Avoid planting native cultivars. Studies show that they are much less attractive to pollinators.)

Gegear says it’s equally important to add some native grasses such as big blue stem or switch grass to garden plantings. Grasses are host plants for some at-risk butterfly species and provide seeds for birds and other wildlife.

With forethought, gardeners can add a native plant or two as space becomes available or even replace an entire section of garden with natives. Making such an effort will support healthy, diverse pollination systems and lend some substance to the popular buzz about pollinator gardens.

Additional Resources:

“Beecology; A Community Scientist Helping Pollinators”; a presentation to NH Audubon by Robert Gegear https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miZEjPqZS98

Article in WildfloraRI, winter 2020 issue; “Plight of the Bumblebee”

Native plant sources: Grow Native Massachusetts https://www.grownativemass.org/; Wild Seed Project; https://wildseedproject.net/

"Pollinators and Simple Actions You Can Take to Save Them”, “a presentation to Climate Action NH by Vicki J. Brown and Judith Saum https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=429481465266104

Native Plant Suppliers:

- Grow Native Massachusetts https://www.grownativemass.org/

- Wild Seed Project https://wildseedproject.net/buy-native-plants/

- Found Well Farm https://www.foundwellfarm.com/