Over-informed on IPM - Episode 022: SWD Monitoring

NOTES

Instructions on salt float method: https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/8/1/23/4157137

My job here in Extension is very different than any other job I’ve had. I’ve always been Extension-adjacent, I’ve always researched aspects of insect biology with application in mind, but primarily a researcher. Before I came to my job here in NH, I had spent nearly two years as part of a national team of researchers working to understand the biology and find ways to manage spotted wing drosophila invasive fruit fly. I touched on this in a previous episode about monitoring SWD and blueberry maggot with Lily Calderwood, the wild blueberry specialist in Maine.

Despite having dedicated several years of my life to studying SWD, I’ve never really had to focus on giving recommendations on what I would do if I was managing a crop. So I kind of looked at last summer as my freshman year, my freshman season. I got a little money from the state IPM program – thank you to the department of agriculture markets & food - to buy some trapping supplies and I got to hire some help to drive around and sample blueberry crops for SWD. I really wanted to know what was better from a logistical point of view, a homemade trap or a commercial trap. I caught up with Abby over the winter to compare notes on what we learned.

Clip from Abby

Now spotted wing drosophila is an invasive pest of small fruit, first reported on the east coast in 2011 and causing serious crop losses since 2012...like in the bajillions of dollars. This fly is closely related to the regular old fruit flies that come into your kitchen with one big difference – well there are two differences, the males have one black spot on the tips of their wings – but the most important difference is that female have a heavily sclerotized, serrated ovipositor. What does that mean? Basically, she’s got saws on her lady parts. While her cousins rely on rotten, broken down fruit on which to lay their eggs, SWD can cut a little hole in the skin of ripening fruit and lay her eggs underneath. This makes SWD and agricultural pest while the other, native species are generally just considered a nuisance.

This pest is unlike most any other insect pest. Not only is this invasive species unchecked by natural enemies, SWD is particularly fecund. With optimal temperatures, a generation can go from egg to egg-laying adult in 10 days. Overlapping generations continue to pop out more and more offspring to result in explosions of populations in the fall, sometimes one trap can catch 1000s of these flies in one day. So fall bearing raspberry is particularly hard hit.

Another weird thing, is that you cannot find this fly in the early spring. It’s super crazy. They’re either not here – like they didn’t survive the winter - or are at unbelievably low levels. So even though these flies like to lay their eggs in strawberry – if given the chance - June-bearing strawberry is rarely affected.

Populations start to grow in late June and early July for most areas of the northeast, which means blueberry and summer raspberry crops are at risk of infestation – depending on when SWD “shows up”. This will vary from location to location and year to year. Monitoring is important for initiating application of crop protection materials. I checked in with my old pals at Cornell to get updated on the hot monitoring gossip

Juliet: I am Juliet Carroll and I’m the fruit IPM coordinator for New York state. I work primarily with berries and tree fruit.

Steve: Sure, I am Steve Hessler. I am the research support specialist in the grape and small fruit program coordinated by Greg Loeb at Cornell Agritech.

Juliet: Yeah, so we started the SWD Monitoring Network in 2013. I was actually just going back through all the data to nail that down. It’s, it’s been quite a number of years-- this will be the eighth season 2020.

Anna: Wow, and what have, what have you learned so far?

Juliet: Y’know, I have learned a number of things. I think I’ll stay on more the science side as opposed to the sociology side of managing a large group of people. It’s been really interesting because the insect arrives across this really long stretch of like 42 to 70-some days in New York state as opposed to, when you think about first-trap catch of other insects, it’s usually a fairly tight period of time. One to two weeks, maybe? And, potentially, the further south you go in a state, the earlier the insect might emerge or arrive in the trap. SWD does not play out like that. It doesn’t think about the fact that Long Island is the furthest south area and the Clinton County is the furthest north area in the network. No. It just decides it’s gonna arrive first in somewhere up near Lake Ontario, or it’s gonna arrive last somewhere down in Steuben County in the southern tier. So, it’s really been an eye-opener in terms of insect biology in that way.

Anna: So, it sounds like the take-home message is that monitoring really matters.

Juliet: It really does. I think it really does and I most of the growers that we interact with would agree that it really helps them to understand when their crops are at risk and I think especially crops that ripen earlier, like Summer Raspberries or the early blueberry varieties. Sometimes they can get away without spraying at all. But, if the insect arrives early, all bets are off. And, it’s the same now with the tart cherry industry and sweet cherries, which have been increasingly at risk. That was the other thing I was gonna say, Anna, that we’ve learned. We’ve learned this insect seems to arrive a little bit earlier, every year, a little bit earlier in the traps. Last year, I caught this insect in mid-May as opposed to our-- usually we think of it as arriving in early June, maybe mid-June.

Anna: For the trapping network that you have, how good is the monitoring data that you’re collecting regionally compared to on-farm. Like, how important is it for farmers to do their own trapping versus relying on trapping data from their neighbor?

Juliet: We would speculate that it is way more important for the grower to monitor on their own farm than to rely on regional. And, I think it goes back to what I was saying about this insect not having any concern for latitude, y’know, geography. I know that Greg Lobe, entomologist here at Cornell, has been trying to get grants to actually do experiments to answer that specific question. I’ve been doing a study of tart cherries and I find every single one of these orchards is in Wayne County. They’re all near Lake Ontario, some are very close to the lake, some are further inland, and the difference is, in first-trap catch just among those orchards that might be eight miles from one another, is pretty significant. One that was quite a bit further inland basically didn’t have to spray at all. They didn’t spray anything for SWD, whereas those that were closer to the lake definitely had to put sprays on to protect their crop from SWD because we were catching there, whereas we didn’t catch in that one orchard. So, long answer to your question. Short answer is, yes, I think it’s really important for growers to monitor on their own farms as opposed to relying on a regional trap catch, but I think the regional trap catch gives them a perspective. It gives them a heads-up-- “hey, it’s here, numbers are increasing, it’s time to get out and, potentially, check the harvest and do a sample, a salt flotation, and look in your fruit on your own farm to see if there’s evidence of infestation that has started.”

Anna: Speaking of monitoring on your own, maybe I’ll shift over to you, Steve. You can throw in your advice on the best methods of monitoring and that could be, like, the best methods because they are the easiest or, like, the less stinky or unpleasant or the best methods in terms of, like, the best information. So, how, how would you answer that question?

Steve: Sure, we’ve, I think since the original detection of Spotted Wing in 2011, we’ve gone through a lot of different types of monitoring tools ranging from apple-cider vinegar—the early years—to a whole wheat bread dough lure, but, certainly though easiest and what’s now probably the standard is a commercially available synthetic lure. There’s a couple different manufacturers, work through Peter Landolt and Dong Cha’s Program. But, it’s been commercialized and that is pretty straightforward—you have a sache type of lure that you insert into a peanut butter jar trap, soapy water as a drowning solution. Growers may want to monitor that a little more frequently, but we find a weekly visit to kind keep tabs on what’s going on gives a good sense of population.

Anna: And, you all have been doing some work looking at how to use that monitoring data. So, once you get really good at identifying your flies, how are you using those numbers to crop management decisions?

Steve: Well, we did do some research, I think it was in ‘14 and ‘15, that related to early detection and using that as a tool. We found really, in raspberries, which was summer raspberry and into fall raspberry, really the monitoring didn’t really provide advanced warning. At the same time, we were monitoring with adult traps, we were also doing salt flotations in measuring infestation and generally found that infestation was either the same or a little ahead of our adult monitoring. Blueberries is a different story. I think, in some ways, we did the same type of research with blueberries and found we were getting advanced warning with monitoring. In some cases, it may have been almost too early, other than it was providing some advanced warning in blueberries, who didn’t really develop a more advanced, sort of recommendation. I think there’s been some work in low-bush blueberries that’s developed some sort of a threshold, but we really haven’t gone that far with high-bush production. Julie was kind of correct in saying the early- and mid-season blueberries—if they’re monitoring and they’re not capturing any traps, they can probably forego any insecticide applications. Some years, that will get them through their season, perhaps. Other years if they’re catching them in those weeks prior to ripe fruit, they better be ready to treat.

Anna: But when it comes to actually using those numbers. I’ve been telling people 1 male/trap/ week – as an average of three traps per site – that would be considered low risk. Then maybe 5-10 males/trap/week would be very high risk…would you agree with that?

Juliet: I would potentially tenor that based on the crop. So, what they’re finding and we’re finding in tart cherries is if, if the, if that crop is ripening in—one SWD, I don’t care what gender it is—gender-neutral, I don’t care, okay?-- it’s time to treat if that crop is ripening. So that’s the threshold they use in Michigan tart cherries and they’re number one in tart cherry production across the nation. In raspberry, I would say the same. You’re looking at one SWD caught and you have a ripe crop out there, or ripening, you’ve got to initiate your program. In blueberries, as Steve alluded to earlier, I think they’re a little bit more forgiving crop. I think in low-bush blueberries, they were looking at a threshold of maybe ten, being when you would have to initiate a spray program if you’ve got ripening and ripe low-bush blueberries in the field. If we ponder, “okay, how susceptible is this crop,” I think raspberries are definitely first, potentially tart cherries and sweet cherries might be second, but often they’ll ripen before this thing arrives and so, in our minds, they aren’t that susceptible because they’re temporally removed, potentially, from the arrival of this insect. And then, blueberries are less susceptible. Then you get into your summer crops-- like elderberry, late varieties of blueberry, fall raspberries, blackberries that might be ripening late in the summer—I mean, at that point, why monitor at all if you’ve got a diversified farm and you know SWD is there, you know that you’re going to need to have an insecticide program in place for SWD on those later-ripening crops.

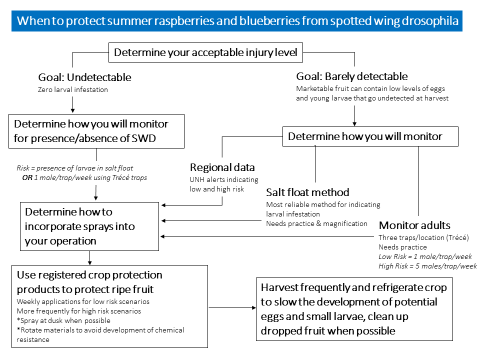

Anna: So I hope I have you convinced that monitoring SWD through July is important for you to determine when to initiate spray programs in blueberry and summer raspberry. What the best way to monitor? That a really tough question to answer. I’m not just pulling that Extension thing where we don’t want to tell you what products to buy. This will really be up to you and the approach that’s right for you. I’ve made a little flow chart that I’ve put into the show notes if you’re into it.

In a nutshell, your action threshold will depend a whole lot on your acceptable level of infestation. If your goal is zero infestation, undetectable, you should monitor ripening crops with a few Trece traps. At least three. Scentry traps are more sensitive and much less selective than Trece traps. So I use Scentry for research purposes but they are not for the faint of heart. They lures a whole bunch of other stuff and finding SWD in there is kind of varsity level stuff. So use several Trece traps and check those traps as often as you can - at least once a week. If you find an average of 1 male/trap/week, go ahead and initiate a 7 day spray rotation. Once you start catching 5-10 males/trap/week, you’ll probably need to shorten that rotation to every 5 days.

I can barely believe that I’m saying this but there is definitely a justification for an acceptable level of infestation. Or what I’m referring to as “barely detectable”. Low levels of young, microscopic SWD larvae will go completely undetected in most cases. As long as you harvest frequently and refrigerate. Several days of normal refrigerator temperatures will knock out these microscopic forms. If your operation can handle “barely detectable” infestations, I would rely on the salt float method to initiate your spray rotation when you find maybe 0.5 larvae per 100 fruit sampled. Out of the dozen or so blueberry operations we monitored last year, most of them got through their season with just one spray. Some of them didn’t spray at all.

Well I hope that helps. I know its not a great situation and the researchers of the world are still looking for better solutions to these problems. So stay tuned!

Thanks to Abby for all her hard work last summer and thanks to the state IPM program for giving her the job. Thanks to Steve and Julie over at Cornell AgriTech and NYIPM. And of course, thanks to Jason Lightbown who wrote and performed our theme music.

Music Credits:

Ashwan – Mauerspechte

Airtone – Common Ground

Image Credits

SWD by Betsy Beers WSU

Related Resource(s)

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010