Appalachian oak-pine forests occur in southern and central New Hampshire below 900 feet of elevation, or on dry, rocky ridges at higher elevations. Here, the warmer and drier climate promotes tree species adapted to drier soils. White pine and oak trees dominate the tree canopy.

Appalachian oak-pine forests occur in southern and central New Hampshire below 900 feet of elevation, or on dry, rocky ridges at higher elevations. Here, the warmer and drier climate promotes tree species adapted to drier soils. White pine and oak trees dominate the tree canopy.

The presence of tree species typical of southern (Appalachian) states sets this habitat apart from the more common oak-pine forest type (also called Hemlock-Hardwood-Pine). Look for black, scarlet, chestnut and white oaks, and shagbark and pignut hickories. Black birch, aspen, pitch pine, sassafras, and yellow birch may also be present. Blueberry, black huckleberry, sheep laurel, and Pennsylvania sedge are typical understory plants. In southwest New Hampshire, mountain laurel shrubs can dominate the understory, while along the Connecticut River and in the Seacoast, Appalachian oaks and hickories mix with sugar maple and white ash on richer soils.

Squirrels may play a key role in re-growing (regenerating) oak stands by burying acorns, often under stands of white pine. They also bury pine cones under oak trees. As a result, it is common to find oak in the understory of white pines, and white pine regenerating under oak.

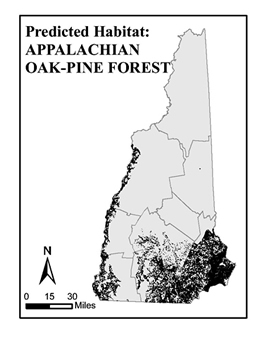

Where are Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests?

Where are Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests?

Appalachian oak-pine forests cover less than 10% of the state, mostly in the southeastern portions, especially Rockingham County, where the largest blocks of this habitat are found. A narrow band also follows the Connecticut Rivernorth from Cheshire into Sullivan and Grafton Counties. Examples of high-quality Appalachian oak-pine forests are in Pawtuckaway State Park in Nottingham, around Great Bay in Durham (Crommet Creek), and at Beaver Brook Association lands in Hollis.

Why are These Forests so Important?

Appalachian oak-pine forests, with their abundance of nut-bearing oaks and hickories, provide a rich food source for wildlife such as ruffed grouse, turkey, black bear, squirrels, mice and chipmunks. In turn, raptors such as northern goshawk feed on small mammals and find nesting and perching sites in white pines in the tree canopy. Near water, white pines provide key nest and perch sites for bald eagles, great blue herons, and osprey.

Threats to Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests

Habitat Lost to Development

Most Appalachian oak-pine forests are in southeastern New Hampshire, coinciding with the highest densities of people. The dry soils in these forests are easily developed for homes, buildings, and septic systems. Much of New Hampshire’s historical Appalachian oak-pine forest is already permanently lost to human development. Large, intact blocks of this forest type are relatively rare, and only 12% of existing forests are permanently conserved.

Land Use History

Many stands of Appalachian oak-pine forest are of the same age, roughly 80-100 years old. They re-grew after farms were abandoned throughout the last century. Many wildlife species of conservation concern found in Appalachian oak-pine forests are attracted to patches of old or young trees within the larger forested landscape. Without a diverse range of ages and sizes of trees, today’s Appalachian oak-pine forests are less diverse and do not support as many of these rare species.

Fewer Beaver Dams, Less Diversity

Prior to human settlement, large complexes of beaver wetlands occurred on the landscape in varying stages of abandonment – from newly flooded sites, to ponds, open meadows and forests. Beaver activity contributed to the patchwork of different tree sizes, types, and ages in pre-settlement Appalachian oak-pine forests. The flat landscape in southern New Hampshire meant that beaver flooding covered more of the landscape than in other hillier parts of the state. Over time, human development encroached on beaver habitats, reducing the ability of beavers to influence the forested landscape, making our forests more uniform and less diverse.

Less Fire, Less Diversity

Less Fire, Less Diversity

Historically, the dry soils and warm temperatures in southern New Hampshire allowed occasional low intensity fires to burn in the forest. These fires were caused by both lightning and burning by Native Americans. Oak trees are relatively resistant to fire and are able to sprout from stumps after a burn, so fire helped maintain a large component of oak in the forest. Without fire, today’s forests likely have a higher proportion of white pine, hemlock, sugar maple and birch, trees less tolerant of fire which don’t provide as rich a supply of nuts for wildlife. Today’s mature Appalachian oak-pine forests may also be denser, as historical low ground fires would have created a more open understory in the forest, important for such species as whip-poor-wills and northern goshawks.

Climate Vulnerabilities for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests

- Although the species that dominate Appalachian oak-pine are tolerant of warmer and potentially drier conditions, and thus believed resistant to climate change, expansion of this habitat is likely to be limited by site conditions. Timing of range shifts will also vary considerably among species, and any migration is also likely to take place over timeframes longer than the present assessment considers.

- Drought-induced water shortages may make this habitat more susceptible to fire, but this is unlikely to significantly alter its extent or composition. Note that fire is still relatively rare even in similar habitats well to the south of NH, so the likelihood of increased fire events is probably low.

- As with other forest types, some forest pests may increase with warmer and/or drier conditions (e.g., gypsy moth), although the potential impacts of these on the overall habitat is unknown.

Click here for the Appalachian Oak-Pine Climate Assessment, a section of the Ecosystems and Wildlife Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2013), an Amendment to the NH Wildlife Action Plan

Stewardship Guidelines for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests

In the face of intense development pressure, land conservation is critical to protect large forest blocks (>500 acres) of Appalachian oak-pine habitat. These large forest blocks are rare, and are critical to protect wide-ranging species such as bobcat, black bear, and moose.

In the face of intense development pressure, land conservation is critical to protect large forest blocks (>500 acres) of Appalachian oak-pine habitat. These large forest blocks are rare, and are critical to protect wide-ranging species such as bobcat, black bear, and moose.- For both conservation and land stewardship efforts, focus on conserving oak-pine habitat characterized by:

- Areas with large trees (>18” diameter) which are important as nutproducers, especially oaks and hickories, and as future snags and den trees used by bats, black bear, and other species;

- Areas with particularly dry soils — look for an open understory and less common trees such as red pine, pitch pine, white oak, chestnut oak, scarlet oak, hickories, and sassafras;

- Areas with a diversity of tree sizes and ages, including patches of young forest, used by New England cottontail, Canada warbler, American woodcock.

- Work to regenerate a mosaic of tree age classes and a mix of tree species to create a “patchy” forest canopy. A full-range of age classes, well-distributed across the landscape, is important to support the great diversity of wildlife dependent on Appalachian oak-pine habitats.

- Provide continual patches of young, regenerating forest habitat to enhance: cover for wildlife, berry-producing shrubs, hardwood stump sprouts, and other key features of “early-successional” habitat (see Shrublands habitats).

- Maintain downed woody material (fallen logs, branches, and leaves) on the forest floor as cover for small mammals, amphibians, and ground-nesting birds. Large downed logs (>18” diameter) provide “drumming sites” used by male ruffed grouse to attract females.

- When conducting forest management activities, maintain some overstory pine to provide additional wildlife cover, perches, seed sources and large future cavity trees. ”Wolf pines” (large, branchy pines with low timber value) can be a good source for these wildlife habitat features.

- Maintain existing cavity trees and snags whenever possible. Cavity trees and snags at least 18” in diameter support the greatest diversity of wildlife species.

- Re-growing oak and white pine after a timber harvest can be tricky. Use carefully planned harvest techniques to regenerate Appalachian oak-pine species. Techniques may include partial “shelterwood” harvests and “group selection” harvests, combined with attention to oak-pine seed sources, seasonal timing of harvest, and planned disturbance of the forest floor to create a favorable seedbed.

- Always consult a licensed New Hampshire forester before conducting a timber harvest on your property. Foresters can employ harvest (“silvicultural”) techniques to regenerate Appalachian oak-pine forest. Understand and follow all laws pertaining to the harvesting of trees near wetlands and waterbodies. Follow established Best Management Practices, and harvest timber near wetlands only when the soils are either frozen (winter) or very dry (summer).

Wildlife Found in Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests

A great many wildlife species use Appalachian oak-pine forests, including those listed below. Be on the lookout for these species, and follow stewardship guidelines to help maintain and enhance these forests. Species of conservation concern, those wildlife species identified in the Wildlife Action Plan as having the greatest need of conservation, appear in bold typeface and link to their wildlife profile from the Plan.

- American woodcock

- Bald eagle*

- Black bear

- Black racer*

- Blanding's turtle**

- Bobcat

- Canada warbler

- Cerulean warbler

- Common nighthawk**

- Cooper's hawk

- Eastern pipistrelle

- Eastern red bat

- Hognose snake**

- Moose

- New England cottontail rabbit**

- Northern goshawk

- Northern myotis

- Ribbon snake

- Ruffed grouse

- Silver-haired bat

- Smooth green snake

- Timber rattlesnake**

- Veery

- Whip-poor-will

- White-tailed deer

- Wild turkey

- Wood thrush

Other Resources for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forests

- NH Wildlife Action Plan habitat profile for Appalachian oak-pine forests, learn more about Appalachian oak-pine forest in NH, including the condition and location of this habitat, the threats facing this habitat, and recommended conservation actions

- More Publications related to Habitats

Photo Credits on this page: Sean Kirwin, Mike Marchand, Frank Mitchell, Ben Kimball, Malin Clyde

Research for this webpage and accompanying Habitat Stewardship brochures was conducted by UNH Cooperative Extension staff with support from the Sustainable Forestry Initiative and NH Fish & Game