‘Winter Flame’ dogwood (with yellow leaves) and two rows of red-twigged dogwood ready to harvest.

Red-twigged Dogwood

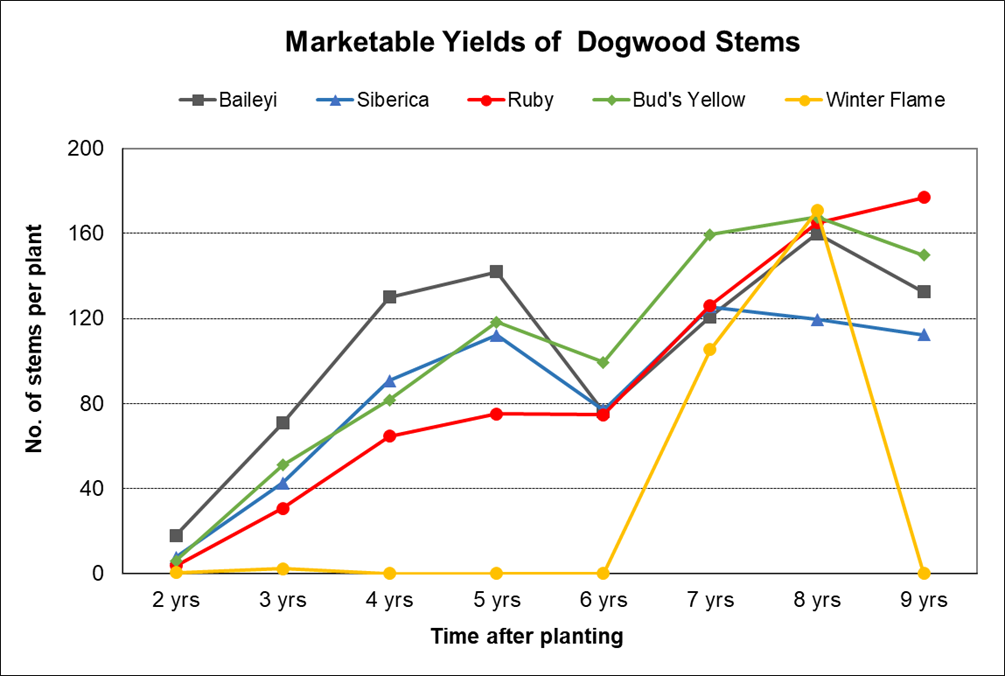

The shrubs known as red-twigged (or yellow-twigged) or red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea, C. stolonifera and C. alba) are adaptable to most soils in our region and are hardy to zone 3. Just as the New England climate provides the best fall foliage, it also provides the best twig colors for fall décor. Red- and yellow-twigged dogwoods develop their rich stem colors when the weather turns cold and the leaves drop in the fall. The cut branches are marketable any time after leaf drop for use in holiday floral arrangements and other fall decorations.

Winterberry Holly

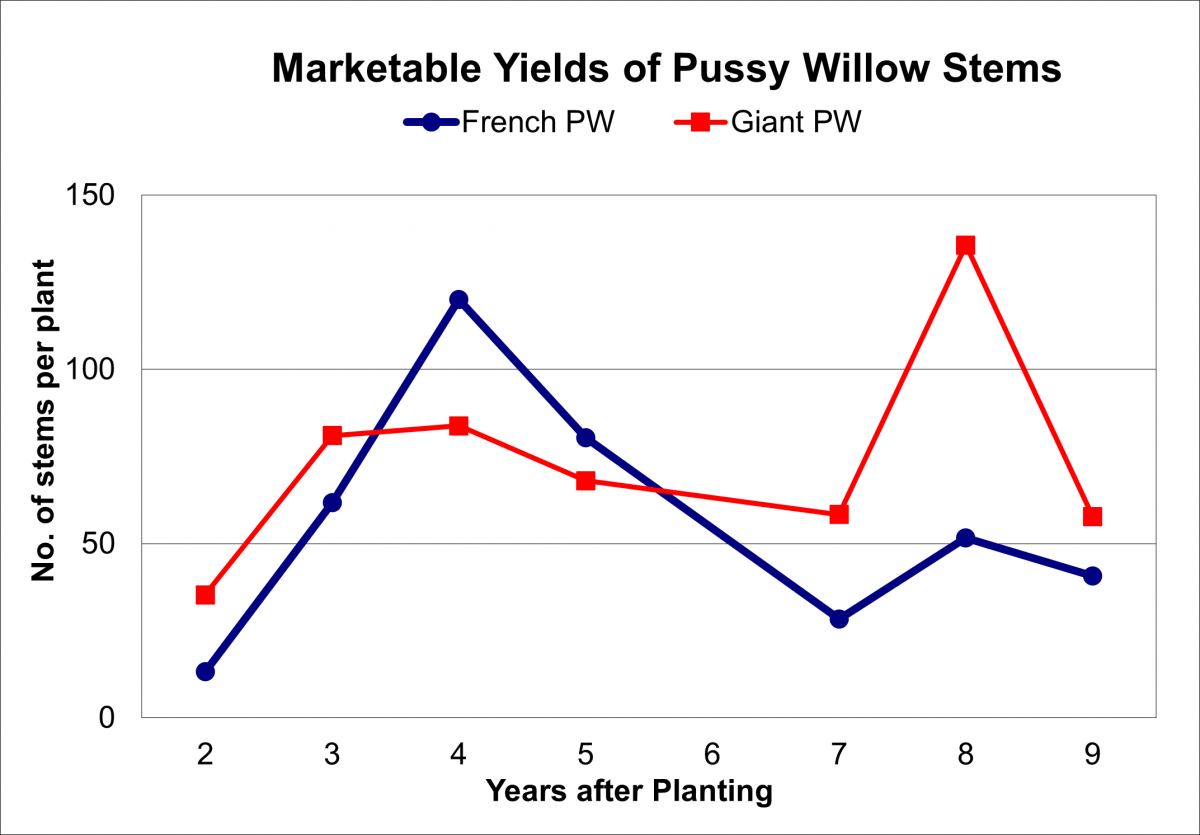

Much of what is currently marketed in the spring is collected from natural stands of the native pussy willow, Salix discolor. They often have weak stems with very few catkins on them. Plant giant pussy willow (S. chaenomeloides) and/or French pussy willow (S. caprea) for your cultivated crops.

canker-infested plantings after several years, when plant vigor and yield decline.

stems dry to prevent them from developing further and releasing yellow pollen.

There are several other species of willows which can be grown for floral and craft use (such as basketry), including the unusual black pussy willow (Salix gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’) with small black catkins borne on deep purple-red stems. Curly willow (Salix matsudana) is easy to grow in zone 5 and parts of zone 4. The contorted branches are of high value, sometimes sold green and sometimes dried. Japanese fantail willow (Salix sachalinensis ‘Sekka’) is another unique, high value crop with good potential for growing and marketing locally . Yields of over 100 stems per plant, most over three feet long, were achieved after three years. Just over forty percent of the stems were fasciated (giving them the flat fan shape desired). The fasciated stems are usually cut before the catkins emerge for use in dried arrangements, but the remaining stems may still be harvested and sold as regular pussy willows, although not as attractive as the giant and French types. There was no winter damage even in extremely cold years, and no evidence of canker diseases or insects on these plants.

Summary