Headwater streams are small streams and wetlands at the highest end of a watershed. Some are so small that they don’t show up on maps. If a river network is the circulatory system of the landscape, headwater streams are the small capillaries that fan into the larger veins and arteries. Headwater streams can start as small forested wetlands, beaver impoundments, or cascading mountain streams, varying according to the topography and geology of the surrounding landscape. Topography and geology influence the speed of water flow, the river bottom material, the plants growing around the streams, whether the stream sometimes or always contains water, and which wildlife species live in or use the stream.

Types of Headwater Streams

Montain Streams

Montain Streams

Mountain streams tend to have large rocks, steep grades, and flash floods. Stream salamanders, brook trout, and certain aquatic invertebrates are well adapted to these dynamic habitats.

Valley Streams

Valley Streams

These streams flow through broad, flat valleys. They tend to be slow-moving and surrounded by wetland plants and shrubs. Beaver activity creates a patchwork of wetlands around the streams, including shrub swamps, wet meadows, and ponds. Wildlife are drawn to these areas including ducks, geese, turtles, amphibians, and fish.

Spring-fed Brooks

Spring-fed Brooks

These small streams flow through glacially deposited sand and gravel and originate from natural springs. Their year-round supply of cool water provides a stable environment for brook trout, particularly during hot weather.

Warm Rocky Streams

The riffles and pools of these rocky brooks are reminiscent of mountain or brook-fed streams, but they are too warm to support cold-water fish. They often flow between beaver ponds in hilly terrain, serving as corridors and hunting grounds for mink, northern water snake, and other wildlife.

Why are Headwater Streams Important?

Many headwater streams are scoured by ice in winter, flood in the spring and fall, and are dry in the summer. Wide variations in water flow and temperature make life difficult in headwater streams. A unique group of plants, amphibians, and insects are adapted to survive in these difficult conditions. These small streams also have a large impact on the health and integrity — both for water quality and wildlife — of major rivers downstream.

Rich Habitats

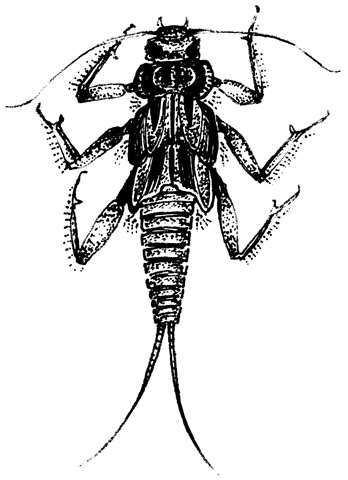

Headwater streams are places where forest and stream habitats converge, leading to high densities of insects around the streams. Stoneflies (see drawing at right), mayflies, and dragonflies, whose larvae live underwater, are found alongside upland insects such as moths, beetles, and grasshoppers. This concentration of food attracts predators from the surrounding forest including northern long-eared bat, red-shouldered hawk, raccoon and ribbon snake.

Headwater streams are places where forest and stream habitats converge, leading to high densities of insects around the streams. Stoneflies (see drawing at right), mayflies, and dragonflies, whose larvae live underwater, are found alongside upland insects such as moths, beetles, and grasshoppers. This concentration of food attracts predators from the surrounding forest including northern long-eared bat, red-shouldered hawk, raccoon and ribbon snake.

Small streams also help remove excess nutrients, such as nitrogen, from a watershed, helping ensure cleaner water downstream. Wood in the small, upriver streams traps leaves and other nitrogen sources, preventing them from accumulating in the lower reaches of the river.

Eastern brook trout (see at left) may live year-round in tiny streams, feeding on both upland and aquatic insects. They may also travel over 20 miles from larger rivers to headwater streams during the fall spawning season or, if the streams have enough water, to find a cool refuge during the summer months.

Refuge streams

Many species take advantage of the relative safety of headwater streams for reproduction. Green frogs and spring and two-lined salamanders lay their eggs in intermittent, fish-less streams. Common white suckers and rainbow smelt, two fish species, migrate every year into small streams to spawn. Headwater streams also can act as travel corridors for wildlife such as mink, otter, beaver, forest birds, and forest- dwelling bats.

The isolation and harsh conditions of headwater streams can also provide native fish with a refuge from introduced species. Natives such as banded sunfish, redfin pickerel, and redbelly dace can thrive in headwater streams, but are over-run by introduced fish in the more stable and often degraded habitats of larger rivers and lakes.

Overlooked streams

Despite their ecological value, headwater streams are often overlooked by conservation efforts and are not covered by New Hampshire’s Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act. Their small size makes them vulnerable to human impacts, particularly those caused by human development.

Use of groundwater by residential or commercial wells can cause streams to dry up. Roads, driveways, and poorly designed or placed culverts fragment streams (like the "perched" culvert in the photo at right), causing sedimentation, and isolate wildlife populations. Runoff from paved surfaces can introduce pollutants, increase flooding, and cause spikes in stream temperature. These and other threats are compounded by the tendency to dismiss small streams because they don’t command the same recreational and aesthetic appeal of larger lakes and rivers, and because they are often considered too small to provide important habitat.

Climate Vulnerabilities of Headwater Streams

- Any increase in the intensity and frequency of flooding events will cause habitat damage and direct mortality to aquatic species, in particular freshwater mussels. This impact would be disproportionately larger in developed watersheds where human infrastructure exacerbates flood damage and limits recolonization.

- Higher temperatures will cause the distribution of species dependent on cold water to shift north and to higher elevations.

- Groundwater resources will be stressed by an increase in evapotranspiration due to climate change. This increase, in combination with water withdrawal for human consumption, may lower summer base flows in some watersheds, causing many perennial streams to become intermittent.

Click here for the Coldwater Streams Climate Assessment, a section of the Ecosystems and Wildlife Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2013), an Amendment to the NH Wildlife Action Plan

Wildlife Found in Headwater Streams

The species listed here are some of the wildlife that use headwater streams. Be on the lookout for these species and follow stewardship guidelines to help maintain or enhance headwater stream habitats. Species of conservation concern—those wildlife species identified in the wildlife action plan as having the greatest need of conservation—link to their Wildlife Action Plan species profile.

- American eel

- Banded sunfish

- Blanding's turtle**

- Bridle shiner*

- Caddisflies

- Craneflies

- Cusk

- Northern dusky salamander

- Eastern brook trout

- Eastern red-spotted newt

- Ebony jewelwing

- Fishing spider

- Little brown bat

- Louisiana waterthrush

- Mayflies

- Mink

- Northern long-eared bat

- Northern water snake

- Raccoon

- Redfin pickerel

- Riffle snaketail

- Spring Salamander

- Stoneflies

- Swamp darter

- Two-lined salamander

- White sucker

*state-threatened species

**state-endangered species

Stewardship Guidelines for Headwater Streams

- Conserving land from development around headwater streams will allow for the natural processes that prevent flooding, maintain water quality, quantity, and temperature, recycle nutrients, and provide food and habitat at the source and downstream. Maintaining intact, undeveloped headwaters may also buffer the predicted higher temperatures and increased flooding and rainfall associated with climate change.

- Incorporating headwater stream protection into town and regional planning through conservation easements and zoning ordinances will have lasting benefits by conserving species, protecting water quality and preventing flood damage.

- When possible, keep development, permanent roads, and driveways at least 300 feet away from streams. Suggested development buffers vary, but a minimum of 300 feet is commonly recommended for protecting wildlife habitat along stream corridors. The benefits of riparian buffers increase with their width.

- Maintain pervious (permeable) surfaces on as much of the landscape as possible. Natural ground is the best filter for storm water, but pervious pavement (as opposed to typical pavement) can reduce stream contamination from storm water in developed areas. Watersheds with as little as 4% of their land area in buildings and pavement have degraded headwater stream habitat.

Roadside salt and sand will drain directly into this stream, degrading water and affecting wildlife

Roadside salt and sand will drain directly into this stream, degrading water and affecting wildlife

- Avoid the use of fertilizers or pesticides near any stream or wetland habitat. Many pesticides are toxic to aquatic organisms. Excess nutrients from fertilizers pollute water by reducing oxygen levels, killing fish and other species.

- Avoid culverts, drains or ditches that discharge storm water directly into streams. Instead, apply designs that filter storm water into the ground, including porous pavement, gravel wetlands, or tree box filters. The UNH Stormwater Center is an excellent resource for the latest research in stormwater management.

- Properly sized and installed stream crossings are critical for restoring or maintaining the function of streams of all sizes. Before installing any stream crossing associated with development, consult the New Hampshire Stream Crossing Guidelines available from the UNH Stream & Wetland Restoration Institute and follow all NH wetland laws. For crossings associated with timber harvesting, see best management practice references below.

- Timber harvesting around headwater and small streams should maintain enough shade and large trees to maintain stream temperatures, filter run-off, and allow for woody material (dead and dying trees, leaves, branches) to naturally fall into streams. For headwater streams, buffers that maintain about 60% of the canopy in a zone as wide as the height of a mature tree (100 feet) are likely to maintain cold water temperatures and woody material in the stream. In larger streams, riparian buffers of 300 feet or more provide more effective wildlife travel corridors and habitat.

- When doing forest management work near headwater streams, minimize impacts by:

- Maintaining dead standing trees, overhanging vegetation, and downed branches and trees to provide moist cover and shade for wildlife and insects;

- Maintaining downed logs in streams to enhance trout pool habitat;

- Consulting the publications Good Forestry in the Granite State, 2nd edition and Best Management Practices for Forestry: Protecting NH’s Water Quality, both available from UNH Cooperative Extension.

- Consult a licensed New Hampshire forester before conducting a timber harvest on your property. Understand and follow all laws pertaining to tree harvesting near wetlands and waterbodies. Follow established best management practices, and harvest timber near headwater streams only when the soils are either frozen (winter) or very dry (summer).

Additional Resources for Headwater Streams

- Eastern Brook Trout Joint Venture (EBTJV)

- NH Reptile and Amphibian Reporting Program

- Good Forestry in the Granite State

- University of NH Stream and Wetland Restoration Institute

- Best Management Practices for Forestry: Protecting NH's Water Quality

- UNH Stormwater Center

- Best Management Practices for Erosion Control on Harvesting Operations in NH

- Other Habitats Publications

Photo credits on this page: Matt Carpenter, NH Fish and Game; Ben Kimball, NH Natural Heritage Bureau; Michael Marchand, NH Fish and Game; King County WA Insect Archive.

Research for this webpage and accompanying Habitat Stewardship brochures was conducted by UNH Cooperative Extension staff with support from the Sustainable Forestry Initiative and NH Fish & Game