Over-informed on IPM - Episode 007: Vegetable IPM - PAR for Leek Moth

Show Notes

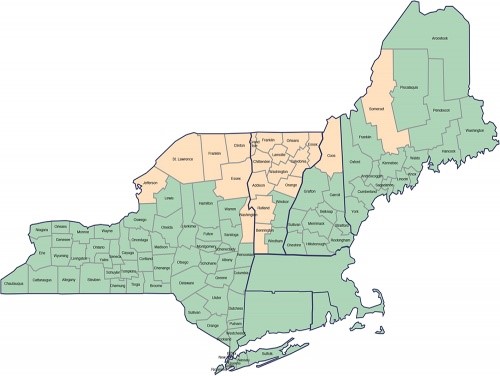

Leek moth distribution as of November 2018 (courtesy of Cornell University)

Transcript

I think I’ve mentioned once or twice how happy I am to be back home in New Hampshire. But sometimes it gets a little lonely being one of only a handful of entomologists in the state. One of the many reasons I started this podcast is that it makes a very good excuse to talk to other entomologists. Nothing fills my heart more than talking to other applied entomologists, especially applied entomologists as dedicated to their craft as my guests on this week’s episode, Vic Izzo and Scott Lewins. This episode might be a little inside baseball but I really enjoyed our discussion. … but first the basics on this week’s pest, leek moth.

There’s a mix of good news and bad news here. Leek moth is not present in most of New Hampshire… or at least not in large numbers. However, it is one of two invasive leaf-mining insects attacking members of the onion family in the north east, which are both looming in on our territory. European native leek moth’s first North American record was in Ontario, Canada in 1993, and has since moved through New York into Vermont and threatens from the North. The other invasive onion pest, allium leafminer, it’s first North American record was in Pennsylvania in 2015 and threatens from the south. Allium leafminer is a fly and, obviously, leek moth is a moth but leek moth adults are tiny mottled brown moths that you probably will not see. You’ll likely see the damage cause by these insects before you see either of these insects – like distorted growth, tunneling with frass aka larvae poop. Larvae of both species mine into onion leaves and they look quite different to me, but they can be most easily distinguished by their pupal form. Leek moth spins a loose cocoon – similar to diamond back moth if you know that one – and allium leafminer pupae are hard-shelled, little, dark brown things – kind of egg shaped. Let us know if you come across either of these guys.

Leek moth can be easily monitored and conventional insecticides do a pretty good job of controlling them. But what if conventional insecticides are not for you? This was the case for Vic and Scott, the hardest working entomologists in Vermont, making it work several different affiliations between them:

Izzo & Lewins intro:

Anna: I asked Vic to tell me more about the Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative and what it does.

Vic: …it does a lot of things, conceptualized by Ernesto Méndez who was the executive director of the collaborative. The concept is basically to apply agroecology in all of its facets, applying ecology to agriculture. Also looking at how it affects livelihoods – applying concepts and how it can best serve farmers. The main focus was originally international, mainly Latin American coffee farmers. Since the last 5 or 6 years, since Scott and I started working with them, we’ve been incorporating a lot of Vermont farmers using something called Participatory Action Research.

Participatory Action Research is an approach that kind of turns the line of academic research inquiry on its head. Scott and I, when we go out and develop a question that we want to research – traditionally it would be something we find interesting or we might identify a problem through an extension agent or a farmer then come up with ideas about solutions we think would work best. We would go out and find a farmer that wants to work with us but we would come up with the experimental design, then someone allows us to do it on their farm

Scott: or just do it on a research farm, which eliminates the production farm from the research model all together

Vic: Yup. What we’ve learned is that we’ve come up with a couple great ideas, and we’ve tested them, and we’ve even seen that they’re successful. Then when we talk to farmers about applying the method, they kind of laugh at us. For a couple reasons – either it’s not cost effective, it doesn’t fit into their landscape…all these reasons they would never adopt it, despite the reason it never works.

Scott: …because the solution came from an academic and not from a farmer..

Vic: …so that’s what we did for a long time. And sometimes we set out to answer questions that weren’t even applied. So with participatory action research, farmers are participating from the very onset of the research question all the way through to applying and adopting it. Even being part of the outreach.

Anna: So Participatory Action Research, which we’ll shorten to PAR, is an approach that put puts the needs of the farmer first so that an adoptable control measure stays in the world of adoptability. I can certainly relate here – as a card-carrying egg-head, I will admit, from time to time, one’s interest in the behavior or ecology of a pest insect can lead one down a magical path to imagination land. Keeping the whole process on-farm, and keeping the farmer in the driver’s seat, can keep our egg-heads out of the clouds. More importantly, farmer collaborators might bring ideas to the table that researchers might not land upon intuitively. Here we’ll use leek moth as an example:

Scott: It’s a caterpillar that feeds on alliums, so leek obviously, onions, garlic…It’s historically been called a leafminer, which drives me as an entomologist nuts, because its not really a “leafminer” it just happens to be in the center of an onion leaf, which is hollow. It feeds on almost all of the leaf but will leave the outside, or the cuticle, intact. You’ll see this window-paning damage on onions, but in garlic and leeks, they feed right though the leaf.

It’s an invasive pest that’s been restricted to Canada, eastern Canada, and a few Northeastern states. The New York growers, for the most part, are conventional. There are some really effective systemic insecticides so all of the interest in leek moth research has basically fizzled out. Up to this point, Vic and I are really the only ones paying a lot of attention to it. As a result, we’ve been able to make a name for ourselves with growers, at least in Vermont, coming up with solutions that would work on a Vermont scale.

The first thing we did was trying to figure out where it was and when it was there. We implemented a monitoring program using pheromone lures throughout the state. What that did was inform us on where it’s a problem and where it’s not a problem, and when they’re showing up. Informing growers on the best timing of spray applications. We’re working with organic growers who really only have one option, which is spinosad (Entrust). Timing of spray applications for organic growing is really crucial. Having that monitoring information was really helpful in providing the timing for spray application.

Vic: I also work quite a bit with gardeners. One benefit with working with a moth species is that they’re nocturnal so they’re only laying their eggs at night. So for smaller scale gardeners, or even smaller scale farmers, a really successful technique is to cover with Reemay or any type of exclusion netting for leek moth at night. Then you can pull that off during the day and doing your weeding and watering, not worry about frying your onions during the day.

Scott: Again with the PAR process, we work with a bunch of growers on a number of different projects. We were talking with one of the growers who we work a lot with about another project. He had mentioned using Trichogramma in sweet corn and how effective these parasitioid wasp were for corn borer. That lead to a discussion – well why not try Trichogramma on leek moth?

Anna: I’m going to jump in here and talk about Trichogramma, and something that makes the PAR model so exciting, because even though this is one of the most highly studied and widely available biocontrol taxa, this wouldn’t have been the first thing I would have thought of if leek moth showed up in my backyard. But because Vermont farmers were already familiar with this parasitoid for the control of other caterpillars, this approach was fully on the table.

There are hundreds of species of Trichogramma but they are all egg parasitoids, meaning they lay their eggs inside the eggs of other insects. They have been found to be effective biocontrols for a very broad spectrum of caterpillar pests, hundreds in fact, including corn borer, corn earworm, cutworm, cabbage looper, armyworm, and codling moth to name a few.

The first description of a Trichogramma species was in North America in 1871 by, my man, the American Entomologist himself, Charles Valentine Riley. Let me digress for a moment to point out that C.V. Riley was the first curator of insects for the Smithsonian Institution and received the French Grand Gold Medal of honor in 1884 for saving the French wine industry from grapevine Phylloxera…granted grapevine Phylloxera had been imported from the US to France a couple decades before that. So we kind of owed them, but honor when honor is due.

Back to Trichogramma, which was first used as a biological control in the early 1900s, first mass reared in 1926 on eggs of grain moth. We know most of what we know about deploying inundative releases based on work with this group. An inundative release is an approach in biological control where a whole lot, one might say an unnatural number of a natural enemy, is release to control a pest insect. They’re not expected to establish and become a permanent member of the insect community so, in this way, these releases are similar to an insecticide treatment. Back to Scott and using Trichogramma for leek moth:

Scott: With Trichogramma you just need to know when eggs are being laid so you can time your Trichogramma releases. Well we already know when the eggs are being laid because we have monitoring traps spread throughout the state. That has led to a collaboration with a company up in Quebec that has a really easy to deploy version of Trichogramma that they’ve been using with their garlic growers. They don’t have a lot of onion growers there so we’ve partnered with them to trial it here in Vermont. So one question that led to multiple solution, most of which came from collaboration with growers.

Anna: Very cool! This is a work in progress so stay tuned for more on leek moth research coming out of Vermont. Us lucky ducks here in New Hampshire will benefit from their work if leek moth becomes a problem so thanks to Vic Izzo and Scott Lewins for their work and a very interesting conversation. That’s it for this week. A very special thanks to Brentwood’s favorite son, Jason Lightbown, who wrote and performed our theme music.

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010