Hemlock Harvests

Hemlock trees (Tsuga canadensis), so common in New Hampshire they are hardly noticed, fulfill a unique niche in the northern forest. A tree of the final phase of forest succession, they are the most shade tolerant of eastern trees.

A conifer, hemlocks have distinctive short flat needles that grow on multiple layers on horizontal branches forming a dense canopy that blocks all sunlight to the forest floor. A mature hemlock forest is a silent, spooky woods with no undergrowth to crackle underfoot. Instead, a thick layer of soft dead duff covers the ground, creating the woods of scary fairy tales. But at the same time, it is the woods of winter refuge for deer who find the tent-like trees that intercept the snow a perfect shelter for winter deer yards.

Hemlock’s little cones that grow at the tips of the branches produce tiny winged seeds that can germinate in shade. The sprouts and saplings grow in shade too – very slowly. But they grow rapidly if surrounding taller trees succumb to insects, disease or natural disasters allowing sunlight to reach the little hemlocks in the undergrowth. They are generalists and grow everywhere, but their shallow roots require consistent moisture and they can die under severe drought stress. They don’t tolerate flooding either.

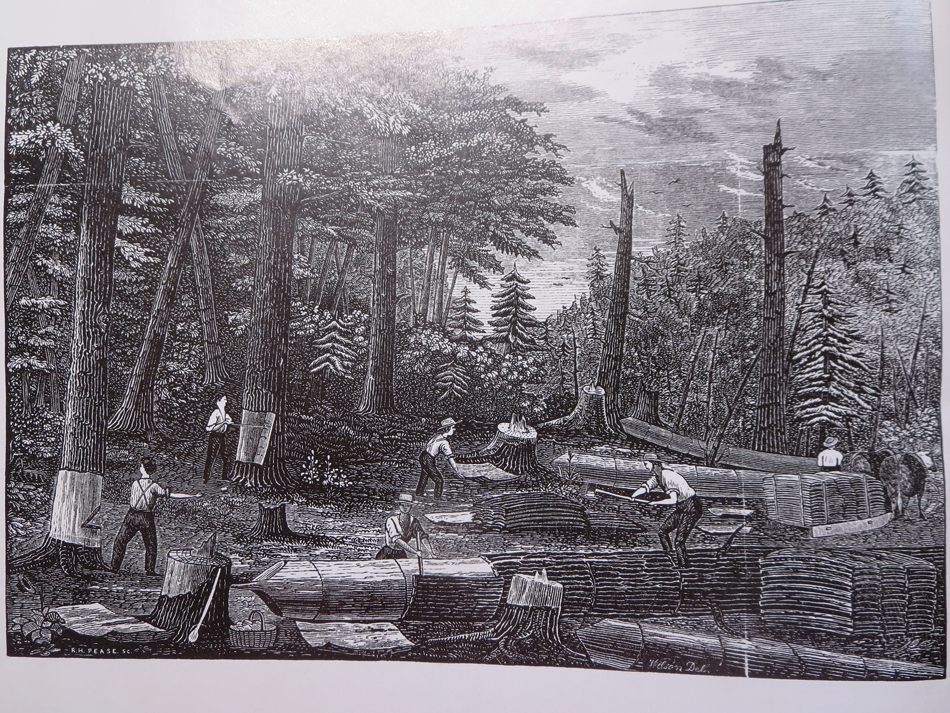

By the late 1800’s, as shoe making evolved from a home craft into a huge New England industry, the need for tannin exploded, nearly eliminating hemlocks from the forest. The high 8% -14% tannin content of hemlock bark makes it perfect for tanning leather. Tannins are an astringent and cause a chemical reaction with the proteins in hides that softens and preserves them to make leather. The historic peak for hemlock prices. was during the during the Civil War era when leather was needed for boots, shoes, saddles, belts, pouches, holsters, etc.

“Tanning establishments gradually crept westward as the forest was cleared and the oak and hemlock bark used in the tanning process was exhausted. Late in the seventeenth century the shipbuilding industry of Massachusetts had so depleted the forests of oak and hemlock that the tanning business soon left the State and went to Maine, Canada, New York, and Pennsylvania, where there were adequate supplies of bark.” https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3519&context=etd

The wanton devastation of hemlock forests that were raped for their bark finally ended with the substitution of synthetic tanning chemicals in the early 1900’s.

Today, hemlock is considered to have a low timber value, and, according to former UNH Extension forester Jon Nute, is the third most common forest tree in New Hampshire, after white pine and red maple. He explained that “a $35 hemlock tree is the same size as a $140 white pine and the same size as a $310 red oak. Hemlock boards have many knots and other defects, which relegates it to lower value uses such as timbers, pallets and paper making.

Curious to see for myself how hemlock is doing at the saw mills with the onset of the hemlock wooly adelgid infestation (a tiny, wingless insect that attacks the needles of the hemlock and is spreading throughout New England, killing the trees) and increased salvage harvests to combat the invasion, I stopped by Wilkins Lumber in Milford and found Tom Wilkins frantically at work. While strapping and loading lumber, he explained that they can’t saw either hemlock or white pine fast enough to fill orders, and customers are happy to use hemlock. The mill is getting the hemlock they need and they have not encountered any shortages yet.

What hemlocks lack in timber value, they make up for in landscape beauty and wildlife habitat value. They are particularly important when growing along the sides of brooks and ponds. The roots control erosion and the branches shade the water to keep it cool, which maintains the water oxygen content to provide a healthy environment for the fish.

When seen in home landscapes as shaped hedges and privacy screens, it is hard to imagine how huge hemlocks can grow. The state champion is 111 feet tall. I have seen hemlocks in the Adirondack Mountains so tall we could hardly see the canopy at the top to tell what kind of trees were growing from the huge trunks. We found some blown-down hemlock trees that had fallen across a trail and been sawed, so we could examine the hundreds of tiny growth rings. The toppled trees were at least 300 years old.

The NH Big Tree Committee maintains a list of state and county champions. To see the state Big Tree list go to www.nhbigtrees.org. If you notice a huge hemlock that looks over 100 feet tall with a trunk diameter over three feet, submit a nomination by going to the Big Tree website. UNH Cooperative Extension, the NH Division of Forests and Lands, and the Society for the Protection of NH Forests sponsor the NH Big Tree program in cooperation with the National Register of Big Trees through American Forests.