By Bo Liu, Director of the UNH Plant Diagnostic Lab and State Extension Specialist, Plant Pathology, and Jeremy Delisle, UNH Extension Field Specialist, Fruit & Vegetable Production

Published February 2024

Blueberry leaf rust is prevailing in the southeastern United States. Until 2023, the disease had been reported in Maine, but not in other New England States. In the summer and fall of 2023, blueberry leaf rust was found widely distributed in New Hampshire, including Merrimack, Hillsborough and Strafford counties. This fungal disease can cause severe premature defoliation of affected bushes (Fig. 1). The fungus causing leaf rust has a wide host range including Vaccinium spp. (blueberry, cranberry, huckleberry), Tsuga (hemlock, spruce (spruce is genus Picea), and Rhododendron (azalea, rhododendron).

Symptoms

Blueberry leaf rust first appears as small, chlorotic to yellow leaf spots on the upper surface of young leaves. As the disease progresses, the spots turn reddish-brown (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Yellow-orange powdery rust pustules (Figs. 3 and 5) develop on the underside of leaves about mid-summer. Infected leaves might curl (Fig. 3). Entire leaves may die and drop prematurely (Fig. 1), which could affect winterhardiness of the canes, and have a direct impact on yield and reduction in flower bud development for the following year.

Fig. 2. The symptoms of leaf rust on the top side of leaves of blueberry plant.

Fig. 3. The symptoms of leaf rust on the underside of blueberry plant leaves.

Fig. 4. Leaf rust spots on the top side of blueberry leaves.

Fig. 5. Leaf rust spots on the underside of blueberry leaves. Spots have a distinct brown edge with typical yellowish orange rust pustules with uredinia and urediniospores.

Causal agent

Blueberry leaf rust was caused by the fungus Thekopsora vaccinii (synonyms: Pucciniastrum vaccinii, P. myrtillus, and Naohidemyces vaccinii), which has several different forms of spores in the life cycle (Fig. 6).

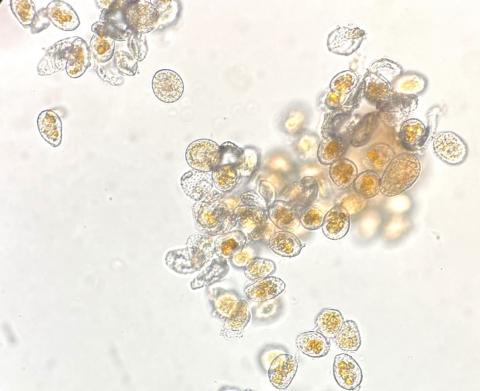

Fig. 6. Yellow uredospores develop on blueberry lower side leaves, which is responsible for the spread of disease.

Life cycle

Leaf rust pathogen has a macrocyclic life cycle. In the spring, airborne aeciospores from hemlock needles (Fig. 7) infect blueberry leaves.

Fig. 7. Hemlock needles were infected by blueberry leaf rust pathogen (Thekopsora vaccinii).

Yellow uredospores (Fig. 5) then develop on the lower side of blueberry leaves and spread the disease among blueberries in a repeating secondary cycle, leading to disease build-up within the planting. In fall, teliospores (the overwintering stage of the fungus) form within the rust pustules on blueberry leaves. The leaves infected with telia drop to the ground where the fungus overwinters. In the spring, airborne basidiospores are produced from germinating teliospores in dead leaves, which infect young hemlock needles and develop aecia. Hemlock is the alternative host for the blueberry rust pathogen to complete its life cycle in colder climates. This is why leaf rust is most prevalent in areas within the natural range of hemlocks, which can serve as an alternative host if located within a half mile of the blueberry planting. In areas where blueberries retain their leaves all year, hemlock trees are not required for the fungus to complete its life cycle.

In summer, leaf rust repeatedly develops on leaves when temperatures are at 20 degrees Celsius (68F). A leaf wetness period of 48 hours is sufficient for infection, and pustules are evident on newly infected leaves 10 days after inoculation. In addition, leaf rust can rapidly increase towards the end of the season.

Management

1. Plant resistant varieties: A Cornell University online report lists Northern highbush varieties resistant to blueberry rust including: Bluecrop, Burlington, Collins, Dixie, Earliblue, Gem, Ivanhoe, Olympia, Stanley and Weymouth. Moderately susceptible varieties are Jersey, Herbert, Berkeley, Blueray and Pacific. Susceptible varieties to blueberry rust include: Coville, Pemberton, Washington and Atlantic. Keep in mind that resistance is a relative term. In NH in 2023, conditions were favorable for leaf rust with excessive moisture and warm temperatures. The variety Bluecrop, listed as resistant in many publications, was observed with severe infection and premature defoliation.

2. Hemlock trees are a native species in New Hampshire and provide important ecosystem services. Hemlocks across the state are under threat from a variety of insects and pathogens including hemlock looper, hemlock woolly adelgid, elongate hemlock scale, and hemlock tip blight. Blueberry leaf rust spores can travel great distances on wind currents making local removal of hemlocks a short-sighted and inefficient response. Hemlocks surrounding existing blueberry plantings should not be removed, and growers will need to utilize other management strategies. Growers planning new plantings can consider proximity to hemlocks as part of site selection.

3. Sanitation is an important part of a successful management plan for this fungus. Raking up blueberry leaves after leaves fall and burning them or burying them deep in the soil can also help to reduce inoculum carryover. Keep in mind that conditions may not be favorable for the development of this disease in every production season. During periods of moderate rainfall or dry conditions, growers may have no issues at all from the fungus. Regular monitoring and proper identification are key to making good management decisions from one season to another.

4. Limit overhead irrigation to reduce leaf wetness.

5. Fungicide application: Numerous fungicides have significant activity against urediniospores of T. minima, but not all of these are registered for use on blueberries. Many fungicides applied to other leaf spots will also have rust activity, such as strobilurins (Abound, Pristine, etc.) and DMI fungicides (Proline, Quash, Tilt, Orbit, Indar, Bumper, etc.). For organic growers, Sonata is one of the few organic fungicides that lists rust on the label.

Inclusion or exclusion of commercial names, logos, products or services does not equate or imply endorsement by UNH Cooperative Extension or the University of New Hampshire.

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010