Over-informed on IPM - Episode 018: Codling Moth

Show Notes

One of my first jobs in entomology, working for Doug Pfeiffer, was to drive down the mountain from Blacksburg, VA to apple orchards in the Piedmont to study codling moth and other tortricids attacking apple. I got to help collect data for a bunch of experiments the Pfeiffer lab had cooking at the time. We evaluated a newish product containing a virus for codling moth, now called Cyd-X. We were also helping companies developing mating disruption for codling moth and oriental fruit moth. We’ve talked about mating disruption in past episodes – in a nutshell, you fill an orchard with so much sex pheromone that the male moths can’t find the female moths and they can’t find that someone special to settle down with and start a family. Well the synthetic version of this sex pheromone is not cheap, so we were helping these companies figure out exactly how much pheromone needs to be put out into orchards.

We were also playing around a bit with delivery systems, usually some kind of plastic doohickey where the pheromone is embedded and slowly released from. One technology back then were these little plastic chips, embedded with pheromone, that could be kind of sprayed into the canopy with specialized equipment on the back of a tractor or 4-wheeler, or maybe even a helicopter if that’s what you’re into.

I remember meeting a guy who was travelling from out west to set up an experiment in the Charlottesville area. He was in a very bad mood as he not prepared for weather… the awesome power of central Virginia humidity had this guy, well… he was coming in hot, both literally and figuratively. Sweating and cursing as he struggled to get his gear to work – he had to retrofit everything for the “HUGE” trees we were working with. They were semi-dwarf trees, by the way. I remember running down to a gas station to get him a Gatorade I felt so bad for him, and thinking, “if this guy has a heart attack I’m going to come back here to call 911.” Oh yeah, I didn’t own a cell phone at this time, if that helps you place this moment in history.

And orchardists have been dealing with codling moth since before cell phones, of course, orchardists have been dealing with codling moth since they’ve been growing apples. Codling moth is the literal worm in the apple. The OG fruit pest. First described by Carl Linneaus himself in 1758, codling moth likely originated in Europe and was first introduced to North America in the mid-1700s. This moth lives just about everywhere that apples are grown. Even though the advent of modern pesticides has allowed other pest complexes may have superceded codling moth as the most important apple pest, thes

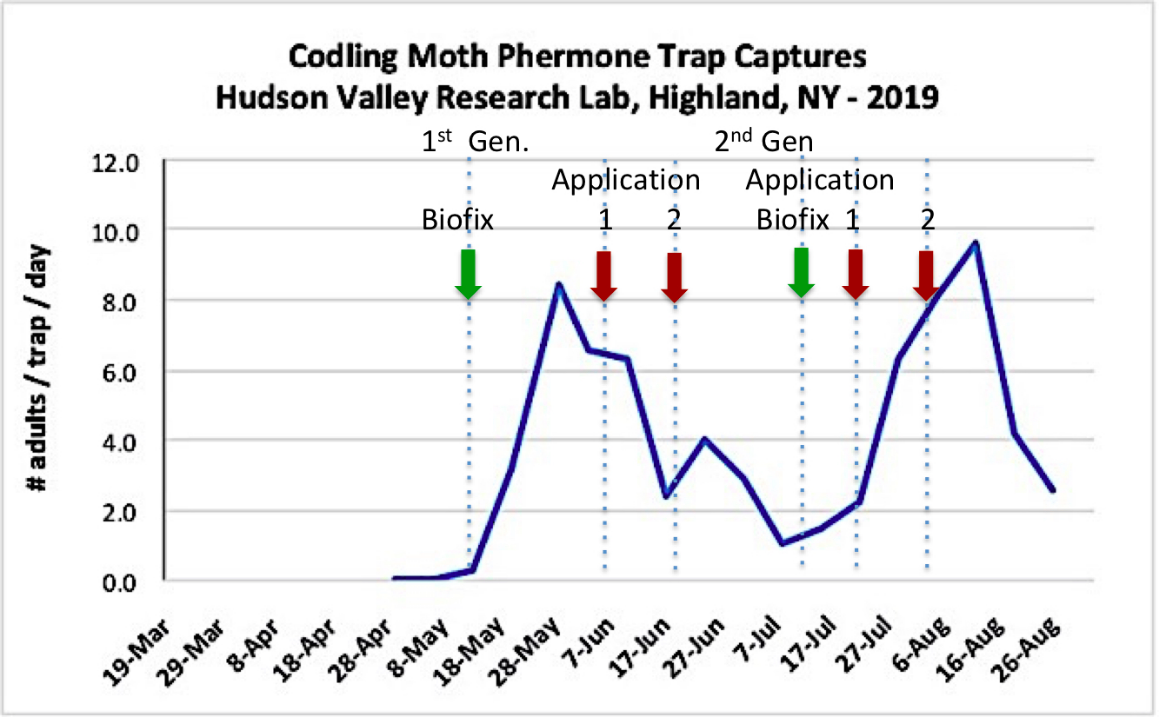

You can find Dr. Eaton’s Pest Fact Sheet 2 on Codling Moth on our Extension website, with some photos to help you with identification, but here are the basics. Codling moth lays its eggs on or near developing apple fruit. The resulting larvae bore into those fruit, all the way to the center of the apple, leaving a tell-tale trail of frass or bug poop. It kind of looks like dark sawdust. Overwintering as a mature caterpillar, codling moth will pupate in the early spring and the first generation flight occurs about a month after that, depending on temperature. These guys are ectotherms after all. Eggs are laid singly on leaves near fruits. Incubation takes 7-8 days. The larvae may feed on the leaves but soon enter into fruits, usually by the calyx (blossom) end. By mid-July, the larvae leave the fruits and pupate either on trees or in the soil. The second adult flight period then begins in late July to early August. The second period of larval feeding is during August and September. Of course the second generation has the greatest potential for damage but timing control measures for the first peak flight period can be really critical for nipping local populations in the bud! How do you do that, do you ask? I needed some help answering this question:

Peter Intro

Anna: If you wouldn’t mind walking through a season with me and like, basically like how do you monitor? How do you make decisions? How do you use modeling tools for codling moth?

Peter: So in New York in the Hudson Valley, codling moth is a reoccurring theme. Most of the damage we’re seeing right now over the packing line, if there’s insect damage it’s going to be codling moth injury. So that said, the growers are taking a real conservative approach. We’re trying to get growers to acknowledge whether or not they have codling moth injury, if they actually know about it. And if historically they’re seeing codling moth injury that exceeds in a wholesale block, 5%— I’m not sure, that’s a moving number, if your block is honeycrisp or any of the premiere varieties that are getting top dollars more like 1% or 2%— so if you’re seeing economic injury from codling moth then this is the way it works for us.

We basically set traps at bloom, pheromone traps for codling moths. One block in ten acres is usually sufficient for us on a commercial farm. And when we have sustained capture, then we work on the NEWA site for monitoring degree of the occurrence and predictive hatch of first generation. That occurs between first and second cover. So that first half of application is going to go on usually at first cover because you’re often spraying for plum curculio at the same time. But the material that you put in for codling moth, we’re recommending that growers use something like Altacor because controlling the first generation is the crux of the climb. If you miss first generation you’re screwed, you know. There’s no catching up for codling moth because it is so endemic and it’s so pervasive throughout the orchard.

So by using Altacor in two applications, so first and second, at the high labelled rate so now the nozzle head comes out, you know. We’re basically going at this insect with both guns blazing. But, those two applications will surround the first generation for the most part unless Debbie Breadth shows up and says “oh what about the B peak”, you know? And then you start thinking, okay what about the B peak? Are you overlapping with that second spray enough of that second wave of adult emergence that you’re able to cover the eggs. And if you’re not, they you really need to keep an eye out on things.

So then you do the same thing for the second generation. This time you don’t need to be as judicious. You look at the trap numbers, see what the trap numbers are. I think that Debbie was using fairly conservative numbers as well—I’m not sure if it was five or ten per trap per week—as the trigger. But if you’re catching less than five per week, then I wouldn’t make an application. But if you’re catching more than five or even exceeding ten, then you’d basically use the sustained trap-catch-capture, with the first insect caught as the beginning of the biofix for this second generation emergence window.

And then putting on applications, if you went with Assail, because you have apple maggot at that point that would be a really good fit because now you’re not putting on anything above and beyond that. If you’ve had just abysmal codling moth applications, then coming in with something like Delegate would be the way to go, or Exirel or if you really want to spend more money, go out to Cyclaniliprole and you know, be done with it.

So I think that Assail still works really well with codling moths, but because we used it year after year after year for apple maggots. Apple maggots have much less of a chance to become resistance because it’s not endemic. It’s the endemic pests, the ones that reside in the orchard that are exposed to this, with each generation, that’s where we might run into problems. And I think that’s what we’re seeing in the Hudson Valley, just not so much resistance, but loss of susceptibility, you know, with Assail. So coming in with Delegate typically is what they do with Obliquebanded leafroller, you know, for that second generation and that sort of cleans up that population. OFM is picked up in there as well.

Anna: So in the words of Alan Eaton, is that clear as mud?

I also have to say it – and I know I’m a broken record but I really mean it. Pesticides must be applied only as directed on the label to be in compliance with the law. Read those labels, guys. And during this conversation Peter and I use trade names of products. It should go without saying, but Extension does not promote the use of individual commercial products. If you have any questions about the active ingredients of these products, especially if you’d like more information on generic products, give your extension specialist a holler. If you’re in New Hampshire, that’s me! Give me a holler!

But what about if you’re looking for an alternative? It’s a little pricey but mating disruption could save you some time and some heart ache. Back to Peter on shifting to mating disruption for codling moth.

Peter: If you really wanted to move forward, then you cross the bridge and you go into pheromone mating disruption. So tracing I think now has thirty eight ties per acre. It picks up OFM and codling moth together. You’re putting those on in bloom and you running the season with a mating structure program. First year you come in and you probably go after that first generation, the endemic generation again. But then in successive years just keep using the pheromone mating disruption program, I think you’re going to be really satisfied with that. So that’s the goal.

Anna: Yeah. So something I’m kind of dancing around with some of my people is that like, especially if you’re thinking about transferring over to mating disruption is that you have to kind of start out with a mop-up year.

Peter: Right.

Anna: So using mating disruption or not you’re going to have years you’re like “My endemic codling moth population is out of control. I have to get really serious. I can’t just rely on collateral damage from my cover sprays. I’m going to start timing it and clean it up as well as I can.” I mean, how often are these mop-up years happen like, what are the indicators that you’re looking for. So if you’re doing mating disruption, what are you looking for to indicate that you have to do a mop up year.

Peter: That’s a good question. I think that if you’re going to transition to mating disruption for codling moth—now I don’t think that would be true with dogwood borer—but I think with codling moth, you should go in with first generation, both guns blazing, on top of your mating disruption. But then for the second generation, so there’s a couple of, I think caveats in this. If you’re not seeing any injury come the end of June from codling moth, then you know that your mop up, whatever that was, two shots Altacor plus mating disruption, did its job. So going into second generation you could probably lay back, you know, on the F16s and just go in with reliance on the mating disruption and then keep an eye on those traps, a close eye on the traps because if all of a sudden you start catching them in the traps. Typically we see one or two, they kind of just stumble into the bar. You know, if you aren’t seeing any catch in there, I’d feel comfortable just moving forward to the end of the season. And you’re going to be using Assail most likely for apple maggot and that will pick up any residual. And if you happen, if you’re really judicious, to time that for that first emergence for the second generation and you’re catching, you’re going after the maggots at the same time, then you’re lining things up a little more effectively, you know, if need be. So that’s the way I would lead towards managing that first year. And I mean the second year, I wouldn’t do anything at first cover or second cover if your plum curculio situation, you reach 308 degree days and you’re all done with the residual needed for plum curculio you’re out of the woods, so to speak.

Anna: So there are a whole bunch of caveats when you’re switching your codling moth management plan to a mating disruption plan but it could be right for you. Like I always say, give your Extension specialist a holler. If you’re in New Hampshire give me a holler. Everyone within the sound of my voice should definitely start reading Peter’s blog. It’s a font of information and he’s really keeps up with posts through the season. Find a link on our website or search “Hudson Valley Research Lab”. You won’t be disappointed. That’s all for now. Thanks to Peter, thanks to Hailee Whitesale for her help with editing and special thanks to Jason Lightbown, who wrote and performed our theme music.

Music credits: Classical Future Milkshake by ramblinglibrarian, snowdaze by airtone (c) copyright 2015

Post Image Credit: Codling moth adult, Whitney Cranshaw, Bugwood.org

Related Resource(s)

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010