Over-informed on IPM - Episode 006: Wild Blueberries and Their Wild Pollinators

Show Notes

Transcript

What’s more American than apple pie? How about a pie made with native wild blueberries? Wild blueberries were gathered by natives well before Europeans arrived on these shores, but semi-cultivated wild blueberries, or low-bush blueberries, became one of our first agricultural industries in the United States. I’m going to take a little break from pest management in this episode to talk about what makes this crop so unique and to talk about incorporating pollinators into IPM. I’m going to jump right into the history with someone who has made a little wild blueberry history of his own.

Frank Drummond, University of Maine: I’ve fallen in love, working over 30 years working with this crop, because it is such a lovely delicious berry that is just part of our ecosystem. There’s been a fair bit written about wild blueberry production and its history. Most of it starts around the Civil War. Almost 200,000 acres were managed then and it was very much a kind of slash-and-burn operation, which was learned from the native Americans. Trains would come up into Maine and they would put blueberries in boxes to ship them down to Boston and New York where they were dried and used by soldiers. That was the height of Maine’s blueberry production. Although at that point, because they were just burning the fields and harvesting them a year and a half later, the yields were not what they are today. They were probably a couple of hundred pounds per acres, where now the average yield is about four to five thousand pounds per acre.

Anna: Well I think it’s really interesting. You know I’m from New England originally, and my family won’t even look at a cultivated blueberry – they’re offended by these enormous apple-sized blueberries.

Frank: Well, I think that’s a common feeling. …and its unlike other crops. In high bush were you might have 5 or 6 cultivars – and I have to say many of those high bush cultivars have introgressed low bush genes in them to give them cold hardiness traits – but because every one of these plants has different genetics, that’s one of those factors that slows down insect population growth. It’s often talked about in IPM courses that plant diversity is really important. Well you see it in action in wild blueberry fields. One plant will be very glossy and have very few leaf trichomes. The plant right next to it is fuzzy, really hairy. The one next to it is really red with lots of anthocyanins. Then the next one is yellow and the next one is green. This diversity is what makes it so difficult for insects to adapt to any one genotype.

Interlude

Anna: Genetic diversity is critical to wild blueberries plants, making them stronger and more resistant to pest organisms – but didn’t I say this episode wouldn’t be about pests. We really care about the fruit right? Well insects have an important part to play there as well but first I want to cover the basics behind how a flower becomes a fruit. Botanically speaking, a fruit is a seed-bearing structure that develops from the ovary of a flowering plant. We presume that the plant puts all this effort into producing a sweet thing around it’s babies so that some animal will come along and eat it, then poop it out somewhere else, thus dispersing those offspring and giving them a little fertilizer in the process.

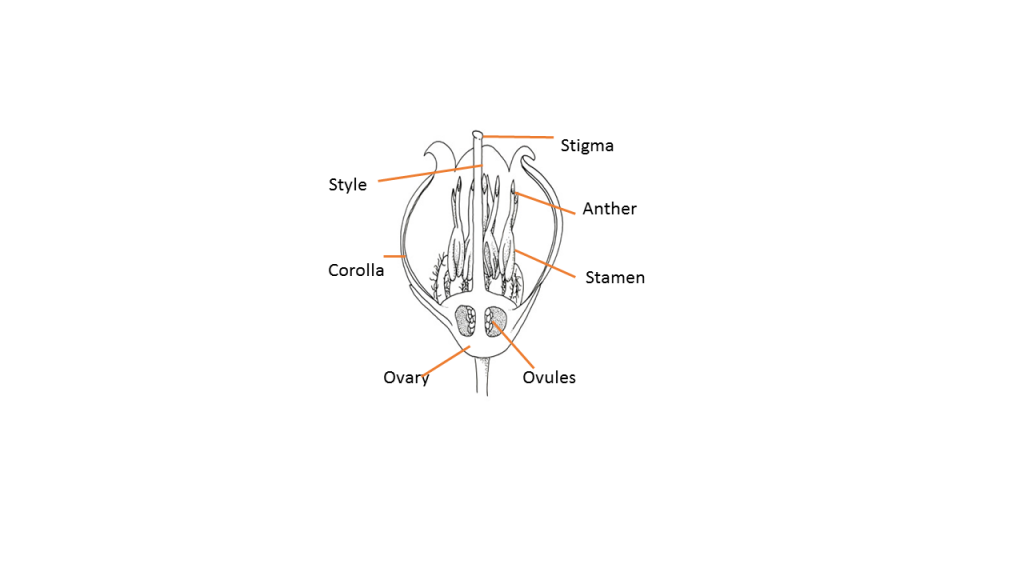

Most fruit develop from a fertilized ovary – an ovary fertilized by pollen. You can think about pollen as plant sperm. Some fruiting plants have complete flowers that have both male and female parts. The male parts are called anthers and the female reproductive system is made up of stigma, style and ovary. Some fruiting plants are self-pollinating, which means that the ovary can be fertilized by pollen from the anthers of the same flower. Some fruiting plants have separate male and female flowers, so there needs to be some mechanism for getting the pollen from the male flower to the female flower. Some fruiting plants must be cross-pollinated in order to fertilize an ovary, in other words these ovaries can only be fertilized by pollen from a different plant entirely. These plants rely on a co-evolutionary relationship that rewards insects with nectar and pollen in exchange for the spread of their pollen and therefore more genetic diversity in their offspring. This is the case for most apples, even though they have complete flowers. This is why apple orchards must contain more than one variety within close proximity. Blueberry can sometimes self-pollinate but we get a much better fruit when blueberry flowers are cross-pollinated. However, even getting pollen out of blueberry flower anthers requires a little help from co-evolutionary relationships with native bees. I’ll let Frank explain:

Frank: The flower of both cultivated and wild blueberry have what is referred to as poricidal anthers. They are anthers that enclose the pollen, that have holes in them, that have to be vibrated to release the pollen once anthesis begins. This makes it very difficult for a lot of animals, insects, even for many bees, to extract the pollen. The poor honey bee tries its darnedest to get the pollen out and generally its more of an incidental venture when extracting nectar. They hit the anthers with their head, with their proboscis. Their heads just barely fit into the corolla. They’re really not adept at extracting pollen.

But many of the native bees – and we’ve documented more than 120 species associated with wild blueberry of the 275 bee species documented in Maine – many of them have particular behaviors or morphology that allow them to extract pollen. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that if a flower is vibrated at 440 Hz with a tuning fork that pollen comes pouring out because that is the frequency that bumble bees vibrate the flowers. They’re highly co-evolved. Bumble bees will, what we call, buzz-pollinate that flower, as well as some of the andrenids. Some of the Osmia will crawl in the flower - they’re much smaller – and they actually drum the anthers with their front legs at a high rate to dislodge the pollen. Some of the halictids do the same, they bat and bang the anthers to get the pollen out.

In studies we’ve done, we’ve found that, on average in a single visit, a honey bee will place about 3 pollen grains on a stigma. A bumble-bee queen about 25-26, an andrenid about 20, Osmia about 18…To put that in perspective, it takes about 12 pollen grains on a stigma, that successfully germinate, to result in fruit.

So honey bees are inefficient compared to native bees on a single bee basis. But the beauty of honey bees, not to take anything away from them, is that you can put 100s of thousands of foraging bees in a field, instantaneously. That massive number of inefficient bees results in a numerical response that can set the crop.

Anna: So a blueberry fruit can be set with one visit from a native bee or 4 visits from a non-native honey bee, they both play a role in wild blueberry cultivation. I asked Frank how the growers in Maine manage this interplay. Do they actually need to bring in honey bees? How do they make this decision?

Frank: I’ll start out by saying that, because so many fruit crops really depend on pollination, growers really pay attention to this. We’ve been able to determine fruit set, which is your potential yield, based on the number of native bees and honey bees that visit flowers. Growers can go into the field and set out quandrants in the field and do timed counts of the bees that fly into the field. The using a simple regression equation, they can estimate their fruit set. If they do this for several years, they can get an idea if they’re getting adequate pollination, whether the native bees are providing adequate pollination or whether they might need to supplement with honey bees. Or, if they don’t want to rely on honey bees because there is a considerable cost, whether it might be better to provide better bee forage around their fields, for the native bees.

Anna: So depending on the composition of native pollinators, wild blueberry growers can make decisions about how many honey bee colonies they want to bring in during bloom. This decision can be influenced by the yield goals of the grower – if they want to push fruit set to more than 80% or if they’re ok with about 30% fruit set. This can be influenced by how long the bloom period is – unfortunately climate change has shortened this period with rainier springs that limit bee foraging. That’s it for this episode and that’s it for our quick break from pest management. Stayed tuned for more on blueberry IPM in episodes to come. A big thank you to Frank Drummond from University of Maine for his help, before he rides off into retirement. And special thanks to Brentwood’s favorite son, Jason Lightbown who wrote and performed our theme music.

End Credits

Bee photo credit: Rob Routledge, Sault College, Bugwood.org

Flower Diagram: Dalphy Harteveld and Tobin Peever

Related Resource(s)

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010