Over-informed on IPM - Episode 008: Plum Curculio (Part I)

Show Notes

Transcript:

From UNH Cooperative Extension, this is Over-Informed on Fruit IPM:

Years ago, as a PhD student, I attended the national meeting of the entomological society of America in Reno, Nevada. I had a funny conversation with a cab driver while I was there – he was asking me why I was visiting Reno and I told him about the meeting – He said “so you study insects huh?...hm…I’m surprised you haven’t figured that out yet?” I laughed and said “well things change…climates change…the crops insects attack change…the tools we use to study insects change…there’s plenty to study” He immediately put two and two together and brought up the pine beetle. A tiny forest beetle that was wreaking havoc in western North America at the time, causing massive deforestation well beyond it’s historic geographic range. Part of this was likely due to milder spring weather which allowed for earlier development of beetle populations, which allowed for an additional generation during the growing season, and therefore an explosion in population. So there was a moment where entomology was shaping this cab driver’s environment and we’re still studying insects. And today’s episode is about a pest of apples, really THE insect pest of apples here in New Hampshire, which we’ve been studying for decades, plum curculio.

There is a rich history of research investigating critical aspects of its biology and developing new tools for apple IPM which we will dig into today, but first THE BASICS. Dr. Eaton has written a great factsheet on Plum Curculio “Pest Fact Sheet # 5” which is available on the extension website, with photos and all the important info but I’ll summarize:

Plum curculio is a key pest of apples, pears, blueberries, peaches, cherries, and (its personal favorite) plums. Now I say key pest because, if you grow tree fruit east of the Rocky Mountains, plum curculio is an insect that will be part of your life. It’s this little, bumpy, brown mottled weevil, very cute (if it didn’t cause so many problems). A weevil is a type of beetle – some people call weevils “snout beetles” because they have these long snouts, kind of an elephant trunk, with a set of chewing mouthparts at the end of these snouts. Adult curculios can and do chew little holes in fruit which is a cause of minor injury later in the fall but the much bigger impact of plum curculio is in egg laying.

Plum curculio overwinters as an adult in the soil or under leaf litter and will emerge in the springtime and will kind of hang out in the orchard, do their thing, eat blossoms leaves, mate. At fruit set, actually when the little baby fruits, or fruitlets, are 6mm or a quarter inch in diameter, females will chew into the fruit for place to lay their eggs. This damage will normally result in fruitlets dropping to the ground in June, which is great for the curculio larvae developing in the fruitlet as they crawl out and pupate in the soil. Also compared to the softer flesh of a growing plum, eggs laid in a growing apple fruit will likely be crushed in the process. Actually this the cause of the characteristic “D-shaped” curculio scar seen on apple fruit at harvest – a healed over scar from that female cutting into the fruit is conspicuous but just cosmetic. There’s no little worm in there. Obviously this is a more serious pest in softer fleshed fruit, like plums, were larvae sometimes do occur in growing fruit. Those feeding scars also open up fruit and expose them to secondary infections by the fungal pathogen that causes brown rot which is quite a problem in peaches and cherries.

Best management practices are to protect fruit trees from plum curculio during fruit set, as soon as fruitlets are ¼” in diameter for a period of about 3 weeks. Protecting trees during this time not only reduces injury due to egg laying but knocking back plum curculio populations early in the spring will help reduce future pest pressure.

Consult your management guide to select your protection approach and, remember, pesticides must be applied only as directed on the label to be in compliance with the law, so read those labels!

So that’s what you need to know about plum curculio management… But entomologist continue to research this insect and its management in tree fruit and some of their findings may shape your approach to management so lets get over-informed on plum curculio IPM!

First let’s dig through the literature:

Although plum curculio is native to the Americas, this species was first described by a german naturalist named Herbst in 1797, and then redescribed and renamed by various entomologist in 1802, 1806, 1819, 1833, 1837, 1843, and on and on…because, well, that’s what people in the business of naming and categorizing species do.

The western limits on its geographic range were established by the 1910s but one of the earliest works we still rely heavily on to this day came from the 1930s.

Paul Chapman, a much beloved character at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva NY, published his 1938 paper “The plum curculio as an apple pest” in the station’s bulletin. As time marched on, our understanding of critical aspects of biology like ovarian development and overwintering behavior, degree day modelling, movement between crop and non-crop space.

And then, in the 90’s things really took off…

Major advances in the chemical ecology of this species were made in several labs, including labs in New York and Massachusetts. Over the years, members of Ron Prokopy’s lab like Jaime Pinero, Tracy Leskey, and Starker Wright learned so much about plum curculio behavior and the chemical odors that it uses to modify its behavior, they were able to modify those behaviors in the field, bend them to their will for the purposes of pest management …but we’ll save that for another episode.

For now I want to come back to Chapman’s 1938 paper which described two “strains” of plum curculio. Up here in New Hampshire, we have the “northern strain” of plum curculio but things get a little more complicated for tree fruit growers farther south. So I’m going to need some help from some of my colleagues…

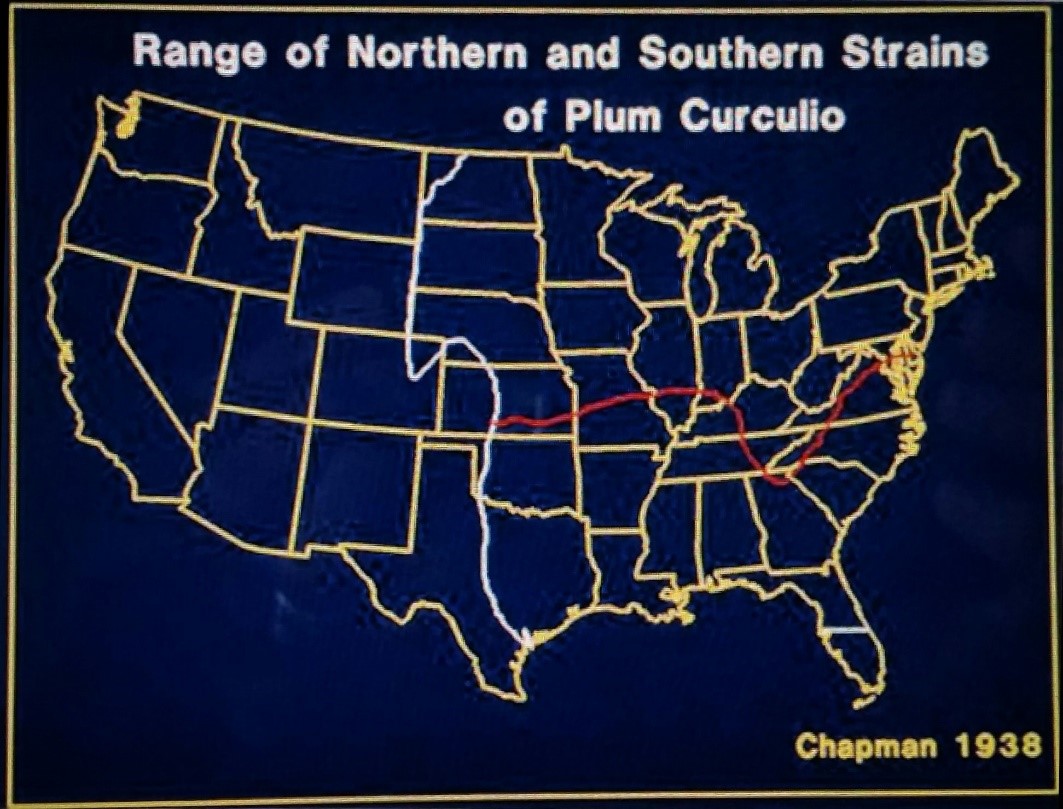

Doug Pfeiffer, Virginia Tech: It’s been known from at least the 1930s that there is a northern and southern strain. Paul Chapman published a map in 1938 showing the distribution of the strains. The dividing line is about the mid-Atlantic area. Although the line follows the Appalachian mountain range, so its not a strict north and south division.

Even in the early years, it was know there was a certain amount of reproductive incompatibility between northern strain and southern strain. An important biological distinction is that the northern strain has one generation. The southern strain is bi-voltine or multi-voltine, meaning it has more than one generation. Usually 2, maybe 3 in the deep south. But there’s only one in the north so its only an early season problem.

In the mid-Atlantic, we have both. We’ve done some sampling in the north, mid-Atlantic, and south. A masters student of mine, here at Virginia Tech, Michelle McClanan, showed that there were genetic differences, using PCR, to differentiate the northern and southern strains. She also show that plum curculio is infected with a symbiotic bacterium, Wolbachia.

Wolbachia is found in most insects and it can do a few different things. One thing is can do is cause reproductive incompatibility - a cytoplasmic incompatibility – if males and females are infected with very different strains of the Wolbachia.

So Michelle found that we had big differences in the Wolbachia. A doctoral student, Zhang Xing, expanded on this. He looked at this at more sites, in more depth, and did mating trials between populations in four different parts of the range, New York, Virginia, West Virginia, and Florida. He showed more detail on the relatedness of the curculio strains, the Wolbachia strains, and he showed that there was – related to these infections – reproductive incompatibility.

Anna: Do you see any reason for us to fear it coming up north?

Doug: That is a very good question. As climates change, with warming winters its possible that southern strains could expand northward. That’s speculation. We haven’t seen that yet. But certainly something to look at. We worry about the invasion of foreign species, like brown marmorated stink bug, spotted lanternfly, spotted-wing drosophila, but its possible for existing species have one strain replacing another, which would be much more difficult to detect.

Anna: So I guess we certainly could consider ourselves lucky up here in New Hampshire that we have only one generation to contend with. One could also say that pest managers in northern climates benefit from the work done by researchers farther south, so lets take a look at what’s going on in the mid Atlantic…

Anne Nielsen, Rutgers University: First of all, plum curculio is a really interesting insect species. It is a native pest, so that differs from a lot of our other key pests in tree fruit. It’s a weevil pest that kind of host switched – from using native plants to commercial production, primarily stone fruit and pome fruit. In peaches, which are important in New Jersey, it is a pretty devastating pest, one of the top pests.

My lab has kind of gone back to the basics. We have been looking at the biology of plum curculio in order to integrate behaviorally based management programs. We have done the genetic analysis (not published yet) and we have the southern strain down here in southern New Jersey. The southern strain has the potential for multiple generations per year. When we look at trap catches, injury on harvested fruit, and we look at the degree day model, all of those confirm that we do have the second generation. The reason that is important is not only from a population growth standpoint but also that having a second generation – especially in peaches – means that you can have contaminated fruit at harvest. You could have a live plum curculio larvae in that delicious-looking peach.

Anna: Do you think there’s any reason for people in northern climates to be worried about the northern strain? Should this be something that we look at in the future?

Anne: Ummm …to be determined. We’re well above his line for the southern strain [in NJ]. Doug Pfeiffer and his graduate student did some research in the early 2000s that identified the southern strain in Virginia as well. They proposed a mid-Atlantic complex, which was a mix of the northern and southern strains. Our data suggest that we have 100% southern strain and that’s consistent with our degree day information.

Something we’re doing right now is taking a look at all the genetic information that’s available for plum curculio – and we’ll be analyzing some of the northern strain populations as well – and reanalysis it with better phylogenetic analysis and see how the clades line up. Just to take another look at the genetics of the population and maybe there is a northern limits. We’re currently analyzing weather station data from the 1930s forward, to see what’s going on. Have we always had the southern strain but just didn’t have the right number of heat units? Or did that southern strain really migrate up and that coincided with warming temperatures? There’s a lot of questions to ask and an exciting part of research going forward.

Anne: So now our approach - and we just got a grant funded on this - we’re going to start looking into border sprays for plum curculio. On top of that we’re doing a multi-lifestage approach. This stems from work Tracy Leskey and Jaime Pinero were doing in collaboration with David Shapiro-Ilan. We’re going to look at plum curculio and its distribution and movement. We’ve already documented in peaches that we have a very strong edge effect. So we’re going to integrate border sprays with entomopathogenic nematodes, or beneficial nematodes, to manage the larvae that are in the ground. The hope is that we can target the application of these nematodes just to certain areas of the orchard – kind of spatially refine the application of these nematodes – because cost is a major consideration. And we need to time application using the degree day model. We’re really trying to integrate multiple IPM tactics here: application of the degree day model, multiple lifestage approach, refinement of insecticide and biological control application to manage this pest.

Anna: SO some cool stuff going on in the world of plum curculio research, then and now. I can’t wait to see what happens next. That’s all for this weeks episode. We will return to the world of plum curculio research and take a deep dive into its behavior and potential behavioral control options for plum curculio IPM. Thank you to Doug Pfeifer of Virginia Tech, Anne Nielsen at Rutgers University and to Jason Lightbown who wrote and performed our theme music.

Related Resource(s)

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010