Inosculation: Making Connections in the Woods

Figure 1. Two hemlocks sharing a branch

Trees can grow in some strange and amazing ways. Last month Greg Jordan wrote about the mystery of burls (check it out here). Greg’s post reminded me of a recent woodlot visit, during which the landowner pointed out two hemlock trees that were connected by a shared branch.

This phenomenon is known as inosculation, which occurs when two individual trees growing in close proximity become morphologically joined. It’s important to note that inosculation is different from grafting in that it is a naturally occurring phenomenon. In contrast, grafting is a horticultural technique used to cultivate a variety of plants, including fruit and ornamental trees.

How Do Trees Become Connected?

So how does inosculation happen? First, we need to know a little about how trees respond to wounds. When the outer bark of a tree is removed or scraped off, the inner tissues become exposed - specifically the cambium (tissue responsible for growth), the xylem (tissue responsible for transporting water and nutrients from roots to upper parts of tree), and the phloem (tissue responsible for transporting food and organic matter throughout the tree). A wound can occur when a branch breaks due to wind, snow, or ice, or when two trunks abrade against each other as they sway in the wind.

Trees respond to wounds by producing callus tissue (scar tissue) that grows relatively quickly to protect the exposed inner tissues. Eventually, the callus growth develops into woundwood, which resembles normal wood with organized cells that form the various tissues (xylem, phloem, cambium).1

Inosculation happens when the friction between two trees causes the outer bark of each tree to scrape off at the point of contact. The trees respond by producing callus tissue that grows outward, thereby increasing the pressure between the two trees. This pressure, along with the adhesive nature of sap or pitch that exudes from the wounds, reduces the amount of movement at the point of contact. The cambia layers from the two trees come in contact and the vascular tissues become connected, allowing for the exchange of nutrients and water, though it is unclear whether the two trees exchange genetic material.2 In 1938, the scientist Henry Baldwin distinguished “true grafts” of inosculated trees as showing “complete union of conductive tissues so that the start of the connection is obscured.”3

Inosculation usually occurs between trees of the same species (figure 1) but it has also been observed between trees of different species (figure 2), though the latter is less common, and sometimes results in “false grafts," which means the two trees have not formed a union of conductive tissues. And although the focus here has been on branches and trunks, natural grafting between roots is common. Some species are more prone to inosculation, such as eastern hemlock, white pine, maples, birches, ashes and American beech.3

Figure 2. Left: Intraspecific inosculation between two white pines. Right: Interspecific inosculation between a black cherry (tree on left) and a red maple (tree on right).

A Source of Inspiration

Naturally joined trees have been revered as a symbol of love and marriage in various cultures and have inspired art and literature throughout history. Thus, inosculated trees are sometimes referred to as “marriage” trees. Interestingly, the word inosculation is derived from the Latin osculum, which means kiss.

For example, the story of Philemon and Baucis from Greek and Roman mythology culminates with an image of the couple as two connected trees. The story goes like this; Philemon and Baucis unknowingly welcome the gods Zeus and Mercury into their humble home. The gods are impressed with the hospitality they are shown, and the warmth and kindness they receive, and reward the couple by turning their home into a temple and making Philemon and Baucis guardians. At the end of their lives, the gods transform the couple into two trees left to grow intertwined with one another; Philemon takes the form of an oak tree and Baucis transforms into a linden.4

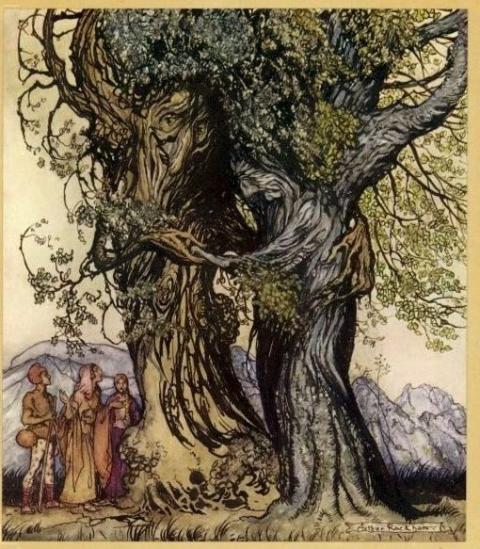

This story, which is over 2000 years old, was the inspiration for Rembrandt’s painting of the same name, completed in 1658, and for the work of Arthur Rackham, completed in 1922 (Figure 3). The story also inspired the poem “Philemon and Baucis” by poet Thom Gunn (1992)5, which starts:

"Two trunks like bodies, bodies like twined trunks

Supported by their wooden hug. Leaves shine

In tender habit at the extremities.

Truly each other’s, they have embraced so long

Their barks have met and wedded in one flow

Blanketing both . . ."

Figure 3. “Baucis and Philemon” by Arthur Rackham, 1922

So, whether you’re interested in finding deeper meaning and inspiration, or you simply like to marvel at the nature and biology of trees, be sure to keep an eye out for inosculated trees next time you’re in the woods. And if you find one, reach out to your county forester and invite them out for a visit. We’re always willing to help landowners connect with their forests.

Have a question about your woods? Contact your Extension County Forester today!

Do you love learning about stuff like this? Subscribe to the NH Woods & Wildlife Newsletter.

A quarterly newsletter providing private woodlot owners in New Hampshire with woodlot management news, pest updates, resources, and more.

1 Luley, C.J. 2015. Biology and assessment of callus and woundwood. Arborist News: pp 12 – 21. https://chrisluleyphd.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Arborist-News-Callus-and-woundwood_Luley.pdf

2 Gaut, B.S., Mill, A.J., Seymour, D.K. 2019. Living with two genomes: Grafting and its implications for plant genome-to-genome interactions, phenotypic variation, and evolution. Annual review of genetics 53: pp 195-215.

3 Baldwin, H.I. 1938. Trees that unite with each other. The American Association for the Advancement of Science, The Scientific Monthly, 47(1): pp 80-85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/16824.

4 Gowers, E. 2005. Talking trees: Philemon and Baucis revisited. Arethusa, 38(3): pp. 331-365.

5 Gunn, T. 1992. “Philemon and Baucis”, from The Man with Night Sweats. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, NY