What to Know about Beech Leaf Disease

In 2024, beech leaf disease was just becoming noticeable in trees across Strafford County and Belknap County. For several weeks, it seemed like I was adding a new town to the beech leaf disease detections map every few days. This summer, trees that were only lightly infested with beech leaf disease last year look drastically different now, with wrinkled, distorted leaves that I’ve been describing as “crispy.” Beech leaf disease continues to spread quickly throughout New Hampshire.

American beech, Fagus grandifolia, is one of the most ubiquitous trees in New Hampshire forests. Because it’s so plentiful and ordinary, rarely achieving the superlatives of other more charismatic species, it’s easy to regard beech with indifference, or in the case of some foresters, even disdain, for its low timber value and tendency to dominate the forest understory and shade out regeneration of other species.

Beech leaf disease in Farmington, NH, early July 2025. Trees that looked like the one above last year seem to look more like this now.

Beech does, however, provide a significant source of food (beech nuts) and valuable habitat (long-lasting cavities in dead beech snags) for wildlife and is an important part of our forest ecosystems. I’ve never personally disliked beech, but I’ve also never been particularly passionate about it either; it’s just kind of there, everywhere, blending into the rest of the forest.

A beech nut

Lately though, I’ve been paying closer attention to beech, looking for signs of a new and potentially quite destructive threat to the future of beech in our forests. Beech trees in New Hampshire have long been affected by beech bark disease, a cankering disease caused by an invasive insect (felted beech scale, Cryptococcus fagisuga, introduced from Europe to Nova Scotia in 1890) and two presumably native fungal pathogens, Neonectria faginata and Neonectria ditissima. Though beech bark disease can and does kill trees, its progression is slow enough that beech has remained a significant component of New England’s forest ecosystems.

Beech bark disease

Now, beeches face a potentially much more significant threat from beech leaf disease, another non-native species. Beech leaf disease (or BLD, since all the nasty forest pests and pathogens seem to get a three-letter abbreviation) is caused by a microscopic worm-like nematode, Litylenchus crenatae ssp. Mcannii.

Beach leaf disease nematodes invade beech buds in the summer and fall, then feed and overwinter in the buds, causing damage that can be seen in the spring. Nematode eggs are dispersed as leaves expand and are likely to be spread by birds, insects, wind, splashing rainwater, and even animals that feed on beech nuts.

View of beach leaf disease nematodes under a microscope.

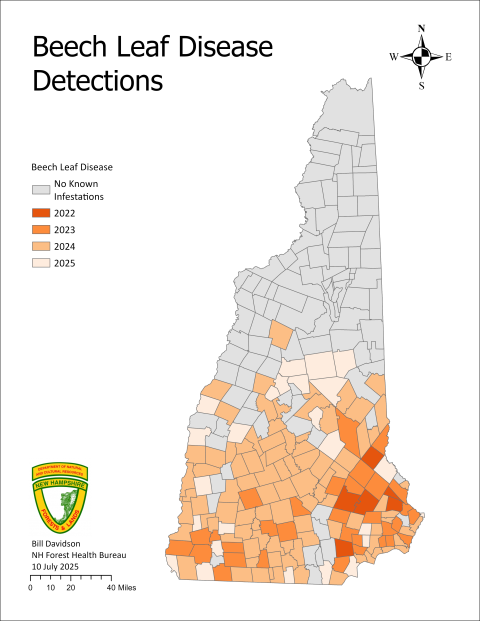

Beech leaf disease is believed to be native to Japan and was detected in Ohio in 2012. By 2019 it made its way east to southwestern Connecticut, and it was first found in Hampshire in 2022. As of July 2025, beech leaf disease has spread as far north as Woodstock and is likely to be present in most areas south of the White Mountains, even if it has not been formally reported yet.

Map from NH Bugs.

Beech leaf disease can be recognized by distinctive bands of darker-colored tissue between the veins of the leaves (often best seen from below), along with curling and distortion of the foliage. The leaves can develop a thick, leathery texture and may drop prematurely. To compensate, some trees may produce a second flush of leaves that are free from nematodes, but are pale and small and less productive than healthy leaves. In trees with a heavy nematode infestation, buds may be killed entirely, leading to branch dieback and eventually the death of the tree. Trees in southern New England seem to be dying quickly (within 3-6 years) after infestation, with the effects of beech leaf disease likely compounded by other stress factors such as drought, winter injury, and other pests and pathogens.

Second flush leaves are nematode free, but pale and small. Photo from July 2025

While beech leaf disease is a significant new forest heath concern, it’s important to know that it’s not the only cause of visible damage to beach leaves. I’ve been seeing some rough looking beeches across the state and not all of them are affected by BLD. A few other organisms that can cause visible damage to beech leaves include eriophyid mites, aphids, and anthracnose.

Beech erineum mite (Acalitus fagerinea), a type of Eriophyid mite, produces velvety patches of erineum galls that can progress from light green to yellow to rusty-red to dark brown over of the course of the season. Erineum patches can sometimes resemble BLD and they may limit photosynthesis in affected leaves, but the effects on the tree are primarily cosmetic.

Anthracnose is a fungal infection that causes black and brown spots and may cause the edges of new beech leaves to curl. Anthracnose is most prevalent when weather conditions are cool and wet during bud-break, which was certainly the case in some parts of the state this spring.

Some species of aphids can also cause leaf curling and damage that resembles the “banding” seen in beech leaf disease.

What should we do about beech affected by beech leaf disease?

While our understanding of beach leaf disease continues to grow, unfortunately there are not yet any treatment options that appear to be effective for beech in a forested setting. The best management strategies for beech are likely to vary, and landowners are encouraged to contact their county forester for assistance.

For significant or high-value landscape trees, several treatment options show promise for reducing and managing beech leaf disease symptoms, including systemic potassium phosphite treatments, foliar applications of a fluopyram-based fungicide/nematicide, and trunk injection with thiabendazole, a fungicide/nematicide also used to manage Dutch elm disease. Each of these options has advantages and disadvantages, and landowners hoping to preserve individual trees should consult with a certified arborist with experience in plant healthcare. The New Hampshire Arborist Association and International Society of Arboriculture both maintain directories of certified arborists. It’s important to note that while arborists do not need to be licensed or certified in New Hampshire, a license is required for commercial application of pesticides.

An arborist from Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories demonstrates thiabendazole root injection treatment at a workshop for foresters and arborists

If you see beech leaf disease, especially in a town where it has not yet been detected, please submit a report to NH Bugs, or reach out to your extension forester if you’re not sure. Beech leaf disease observations in New Hampshire on iNaturalist are also being monitored and cross-referenced with other reporting.

Learn more:

- NH Bugs

- Looking for American Beech (August 2019)

- New Research into Potential Impacts of Beech Leaf Disease (BLD) to Begin at UNH (April 2023)

- The Future of Beech in New Hampshire (Taking Action for Wildlife, January 2025)

- Updated Beech Leaf Disease Biology and Management (Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, May 2025)

Have a question about your woods? Contact your Extension County Forester today!

Do you love learning about stuff like this? Subscribe to the NH Woods & Wildlife Newsletter.

A quarterly newsletter providing private woodlot owners in New Hampshire with woodlot management news, pest updates, resources, and more.