Over-informed on IPM - Episode 016: Brown Marmorated Stinkbug (BMSB) Part I - when to freak out

Show Notes

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve seen this week’s bug, maybe in your garden, maybe in your window sills, maybe there’s one up in the corner of your ceiling looking at you right now. It’s brown marmorated stink bug, or BMSB …Actually forget what I said about those of you living under rocks because this bug likes hanging out under rocks, so you would have seen them there too.

BMSB is an invasive insect that was accidentally introduced to the US some time ago. It was first reported in Pennsylvania in the 90’s where it was mostly considered a nuisance pest. By the early 2000’s it was considered an agricultural pest in the mid-Atlantic states. In 2010, tree fruit and vegetable growers saw catastrophic losses due to BMSB damage. Piercing-sucking feeding by huge numbers of stinkbug adults and nymphs leaves fruit bruised and beaten up, sometimes shriveled, definitely unmarketable. It’s really hard to distinguish BMSB feeding damage from native stink bug damage, other than the sheer scale of damage when outbreaks happen. BMSB has remained a serious pest for mid-Atlantic growers and parts south - in crops like peach, apple, sweet corn, tomato, peppers, raspberries, snap beans…holy moly, you name it and this stinkbug loves it.

Adults overwinter in protected locations, sometimes in your house. During this overwintering period, they are not eating or reproducing or laying eggs, nothing like that. They are kind of stinky but they’re not harmful, they don’t want to bite you. They are just hanging tight in a kind of physiological stupor until the spring comes. If you don’t want to squish BMBS you find in your house, you could suck them up in a vacuum cleaner?

Anyway – like I said - they overwinter as adults, which emerge from overwintering habitats in the spring. They take to the trees to lay their eggs, relying on a pretty broad host range of trees including fruit trees as well as many other forest and ornamental trees. When nymphs hatch they scamper all around – I’m only kind of joking when I say scamper – baby stinkbugs can’t fly but they can cover quite a bit of ground. They scamper all around feeding on the fruits of an incredibly broad range of host plants and become the adults that will overwinter. Just one generation a year.

Up here in New Hampshire, BMSB has been detected but has remained firmly in the “nuisance” category. Our George Hamilton – and since we’re talking about BMSB I should make it clear that we’re talking about George Hamilton of UNH Cooperative Extension and not the George Hamilton of Rutger’s University – and isn’t it funny that there are so many George Hamilton’s in this story? Anyway, our George Hamilton has been vigilant in his monitoring efforts here in the state, monitoring major fruit growing regions using pheromone baited pyramid traps and turning up pretty low numbers. More on trapping in another episode but he detected a big jump in numbers last year that had me wondering: When should we start freaking out? So I called up my buddies that know better than I do:

Rob Morrison, USDA-ARS

Anna: Rob is currently researching pests of stored products and I’ll return to this topic in later episodes, but Rob spent many years in the BMSB trenches.

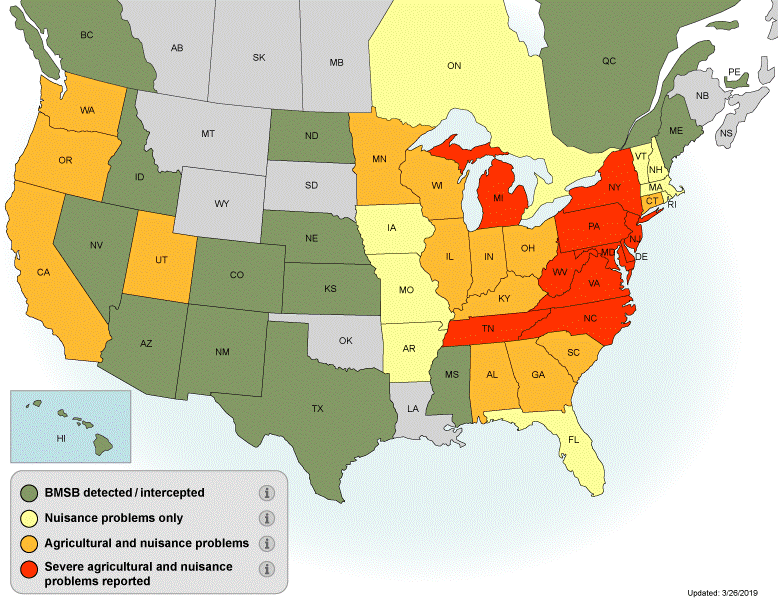

Rob: I’ve had to compile all of the BMSB distribution maps over the years, by the first BMSB working group and by the SCRI project, and there’s a clear trend. There’s first detection, then you have the nuisance problems, then it escalates to agricultural problems, then to severe agricultural problems. If you compile these maps you can see a kind of stop-gap animation, where infestations are spreading out from the mid-Atlantic basically. Since its introduction, it’s quickly expanded to the south, to Georgia, South Carolina, then to the west, in Michigan, Ohio, Illinois. It seems like for a long time it’s been stationary in New England states, but it’s probably just a matter of time before you start having larger problems.

When you first start seeing nuisance problems, populations are often concentrated around urban areas. When you start to see larger numbers farther away from urban environments and house, it starts to become a bigger problem. My advice would be to set up some traps with a little distance from structures and if you see an increase in capture there, it would be pretty concerning.

Anna: So our cold climate and rural living might have helped us up here in New Hampshire so far but who knows what might happen next. We certainly do see more nuisance BMSB problems in the seacoast areas where the climate is both more mild and there are more people with warm buildings for stink bugs to hunker down in for the winter. I asked for more advice on how to know when you have an agricultural problem with BMSB from folks who work down near the epicenter of the invasion.

Daniel Frank, West Virginia University

Anna: What’s the status of BMSB in West Virgnia?

Daniel: Well, it depends on where you are. Most of our tree fruit is grown in the eastern panhandle of the state – we have four counties there. Three of those counties, right there by Virginia and Maryland, they get hit hard by brown marmorated stink bug. Of course it depends on the year. Some years are higher than others. There’s another county that’s just over the mountains and they don’t get hit hard by BMSB. Its definitely a more sporadic pest. Most years they really don’t have major issues with it.

Anna: Do you have any ideas as to why there’s such a big different in severity?

Daniel: That’s a question I’ve been wondering about myself. Maybe they just can’t make it over that mountain range? That’s the only big difference I can think of between those two areas. I don’t know.

Anna: At what point should we freak out? Or what would be an indicator to you that you have a problem with BMSB?

Daniel: Just in my own orchard and in some of my research orchards, I’m out there sampling and I get an idea of what the fruit looks like. If I’m starting to see stink bug damage, that lets me know that there’s an issue.

Last year was kind of a weird year for us. It was just so wet, we did have stink bug populations until really late in the season. Maybe late September was when we really started to see them in the orchards. When I do the sampling I look at the leaves and the branches. If you’re going out there and you’re not seeing any stink bugs, that’s good. That’s a low population. When they really start becoming a problem, you’ll notice them in the trees, you’ll see them flying around. You’ll start seeing the damage too.

Anna: So I don’t know if that makes any of you any happier to hear that if you have a problem with BMSB you’ll know it but it sets my mind at ease that we’ve keeping an eye on things and will be able to act on serious problems when they arise.

While I am going to return to the topic of what to do if we do see agricultural injury, and feature much of Anne Nielsen’s work at Rutgers University, I wanted to ask her the same question when to freak out question. If Rob Morrison spent a long time in the BMSB trenches, one could argue that Anne Nielson was the one that dug those preverbal trenches during her PhD at Rutgers with George Hamilton.

Anne Nielsen, Rutgers University

Anne: Ok, so a little background about New Hampshire. Something that’s really exciting, from a scientific perspective. At Rutgers we developed an E-DNA tool, or environmental DNA. These are minute traces of DNA that are present in the environment. So it can be things like fecal matter, or frass, from an insect. It can be cast skin. It can be a feeding site. So Rafael Valentin, who was a graduate student now a post doc, developed a technique to detect environmental DNA in agricultural systems. Before his work, it had only been done in aquatic systems. So this was a first. It was kind of exciting! We actually did this at a farm in New Hampshire as our “unknown BMSB presence” site.

What we found, using the wash water vegetables were cleaned in before going to market, we were able to detect the presence of BMSB – that’s the presence of BMSB E-DNA – before the pheromone traps did. The year after we detected it, the populations were unfortunately higher.

Anna: Ok, so I hope I have you convinced that we’re on the scene. We’re keeping an eye on the status of BMSB in New Hampshire. Of course I asked Anne what to make of the fact that last year some of our pheromone traps captured more than 10 bugs, which is the kind of rule of thumb in terms of threshold. I asked her should we freak out now?

Anne: It’s not clear cut. There’s not a direct relationship between “I have 5 bugs and then I have 5% injury… or 25% injury” because they move. They move through the orchard, through the farm, through the landscape, and so its hard to make these direct correlations. But if you’re catching them in traps, you need to be aware of the potential for injury.

You don’t need a lot of bugs to create injury because, especially in peaches, they will stay there throughout the entire growing season. When we first started studying this in New Jersey back in 2005 or 2006, growers didn’t know they had BMSB. I had seen a couple on their farm, visually, but numbers were really low. I still documented stink bug injury of 25% at harvest.

Anna: Holy moly! 25% injury at harvest! Well even though we did catch more BMSB in pheromone traps in New Hampshire last year, I didn’t see much of any stinkbug damage at harvest. So the take home here is that you should be aware of the potential for crop injury due to the this invasive pest but don’t freak out! Not yet!

IPM specialists down in the mid-Atlantic states spent decades working towards pretty stellar IPM programs…convincing their growers to pull back on calendar based sprays, use thresholds, rely on biocontrols for aphids, behavioral controls like mating disruption for key pests. Those of us who witnessed the outbreak of BMSB saw that work kind of go down the drain as it required the return of heavy reliance on broad-spectrum insecticides throughout the summer season to protect their crops. But don’t be forelorn! We will return to this topic to discuss monitoring strategies and Anne Nielsen will perform a little CPR on mid-Atlantic tree fruit.

Thanks to Rob Morrison of USDA, Daniel Frank of West Virginia University and Anne Nielson of Rutgers University. And special thanks to Brentwood’s favorite son, Jason Lightbown who wrote and performed our them music.

Related Resource(s)

Complete Show Episode List

Extension Services & Tools That Help NH Farmers Grow

Newsletters: Choose from our many newsletters for production agriculture

Receive Pest Text Alerts - Text UNHIPM to (866) 645-7010