Watch the video for a summary of key findings.

Written by Amy Gaudreau, UNH Cooperative Extension. June 2023.

This publication was produced as part of the Women in the Woods project by the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension (UNHCE), NH Timberland Owners Association (NHTOA), and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (SPNHF). Funding for this program is provided by a Landscape Scale Restoration Grant, U.S. Forest Service.

UNH Cooperative Extension (UNHCE) is a public institution with a longstanding commitment to equal opportunity for all. It is the policy of UNH to abide by all United States and New Hampshire state laws and University System of New Hampshire and University of New Hampshire policies applicable to discrimination and harassment. UNHCE does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, veteran’s status, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, or disability in admission or access to, or treatment or employment in, its programs, services, or activities. Women in the Woods programming is open to all participants, regardless of gender or sex.

ABOUT

Women-owned and managed forests provide diverse public values, including wildlife habitat, forest products, water quality, climate mitigation, and recreation. However, many women may lack the skills, knowledge, and confidence to make informed stewardship decisions and effectively manage their forestland. Women in the Woods, a project of the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension (UNHCE), NH Timberland Owners Association (NHTOA), and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (SPNHF), seeks to support women landowners, managers, communities, and natural resource professionals across New Hampshire. Women in the Woods uses a needs-based approach to develop and provide skills-based training and assistance for stewardship planning to a network of women forestland owners and managers across New Hampshire. The goal is to provide a historically underserved and increasingly important audience in forestry outreach and technical assistance with increased capacity to protect, manage, and enhance New Hampshire’s valuable forest resources. In this publication we will use the term “women.” We recognize that this does not capture everyone’s identity in our expansive community.

BACKGROUND

Few studies exist in the United States, particularly in the Northeast, that examine the role of women in forestland management. Despite some research on this topic, there is still much to be discovered about why women acquire land, their beliefs, limitations, barriers, goals, and how these factors differ from their male peers. In the United States, 58% of forest ownerships are typically co-owned by a man and woman who are likely married.¹ Men are traditionally associated with forestland ownership and management, but the number of women who help make decisions for forestland is often underestimated.² Women are the primary decision makers for 31% of forest ownerships in the United States, which equates to approximately 44 million acres of forestland.1,3 That number is increasing, and the upward trend is likely to continue. In 2006, the percentage of women acting as primary-decision makers was 11%, doubling to 22% in 2013.⁴

Despite this increase, current systems (e.g., information dispersal, community support, and lifestyle responsibilities) do not recognize the impact women’s decision-making can have on forestlands.² Because private landowners—including women landowners—make impactful decisions across the landscape, it is important to understand the social context; who owns the land, why do they own it, what have they done in the past, and what do they plan to do in the future?⁴ Understanding relationships between landowners’ ownership characteristics, attitudes, intentions, and history of forest management activities is critical for developing effective outreach strategies.

Women-managed Forestland

In New Hampshire, non-industrial private landowners oversee approximately 73% of the State’s forests. The decisions made by these stakeholders have an enormous impact on our forests. Specifically, women landowners in New Hampshire contribute to management decisions on over 1.8 million acres of the state’s forestland and are the primary decision makers on approximately 23% (429,000 acres) of private forestland. The health of New Hampshire’s forestland is defined by the ability of private landowners to make informed management decisions on their property. Encouraging landowners to manage their land with sustainable forestry, land use, and climate change in mind will address issues related to forest regeneration and tree diversity. New Hampshire forests also face threats of fragmentation which negatively impacts biodiversity. Without proper mitigation and response, our forests will continue to degrade. Nationally, an increasing trend of women forestland owners becoming primary decision-makers for their land has been observed.⁴ Despite the increasing role of women decision-makers, little is understood about their management behaviors and attitudes.1,5 Valuable insights can be learned about how landowner attitudes influence involvement in forest management programs.⁶ In general, women are believed to have different attitudes and motivations when it comes to forest management than men.5,7,8 Research has also shown that men and women have different preferences in workshop topics and attributes (e.g., interactive, webinar, PowerPoint, family event).⁹ Additional research has revealed that women face more land management challenges than men, and current systems do not recognize the differences between men and women’s decision-making.² Other research has found that women forestland owners feel that their biggest challenges when purchasing or inheriting land is their lack of management knowledge and limited access to natural resource professionals.¹⁰ Compared to men, women in forestland management roles can suffer from feeling unqualified or incompetent, known as imposter syndrome, and may feel overwhelmed after initially acquiring land.¹¹ Additionally, traditional management activities may not resonate with women forestland owners and therefore result in less participation in forestland management practices.1,2 Women in the Woods, a project of the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension (UNHCE), NH Timberland Owners Association (NHTOA), and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (SPNHF), aims to connect women forest landowners, managers, and stewards with the resources, skills, and community they need to make informed stewardship decisions that promote healthy forest resources. Additionally, UNHCE, NHTOA, and SPNHF work across the State to address crucial resource issues identified in the 2020 New Hampshire Forest Action Plan (NHFAP). The NHFAP is a 10-year strategic plan that provides long‐term, comprehensive, and coordinated strategies for addressing challenges and opportunities. Three strategies related to the Women in the Woods project as outlined in the NHFAP include:

- Promote and support sustainable forest management on private lands that takes in consideration, along with the production of high-quality forest products, multiple objectives such as forest recreation, wildlife habitat, watershed protection, resiliency, and providing ecosystem services.

- Support comprehensive programs for landowner education offered by UNHCE, natural resource agencies and private conservation organizations such as NHTOA and SPNHF.

- Support outreach events that target new, nontraditional, and underserved audiences that promote and increase the understanding of the importance of New Hampshire’s forests.

IDENTIFYING NEEDS

Supporting outreach for underserved audiences is one NHFAP strategy the Women in the Woods project focuses on. Nationally, women are a historically underserved and increasingly important audience in forestry outreach. No prior research has been identified in New Hampshire to assess the needs and experiences of women who participate in forestland management.

In summer 2022, UNH Extension anonymously surveyed self-identified women and gender nonconforming forestland owners and managers 18 years of age or older. The survey was exclusively online through the software Qualtrics and was distributed by social media, websites, e-newsletters, and e-mail. The survey consisted of 46 questions of Likert scales, multiple selection responses, closed-ended, and open-ended questions. The results in this report are based on 415 responses to the survey completed between July and September 2022. Results described exclude certain responses—such as those who made irreverent comments, self-identified men, and respondents who completed less than 60% of the survey.

This survey aimed to identify:

- Reasons for owning or managing land

- Ownership and forestland characteristics

- Previous management activities

- Future intentions

- Perceived barriers and challenges to forestland management

- Participation in natural resources programs

- Experiences with differential treatment based on gender

- If a women-focused approach is appealing

- Valuable aspects of educational programming

- Needs for educational resources

- If key characteristics (e.g., ownership type, acreage size, knowledge, learning-style, decision-making position) influence behaviors and attitudes towards forest management

The results included in this report are a summary of key findings. A complete copy of the survey questions is included in the Appendix.

SUMMARY FINDINGS

Women as Landowners and Managers in New Hampshire

Key Findings

- 68% of respondents who are not aware of resources available to help them get started with management passively manage their land.

- 66% of respondents do not have a gender preference for an instructor, while 22% prefer a woman instructor.

- 50% of respondents are very likely or somewhat likely to attend women-only workshops.

- 48% of respondents have a forest stewardship management plan for the land they own or manage.

- 35% of respondents have experienced differential treatment based on gender in an educational setting.

Demographics

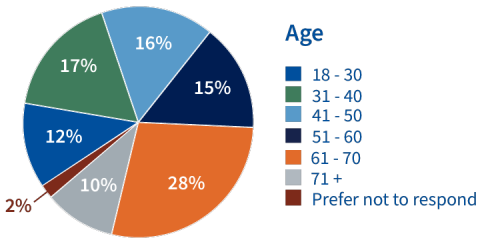

Data in this report includes 415 responses from women and gender nonconforming individuals from 154 towns in all 10 New Hampshire Counties (figure 6). Most respondents self-identify as women (98%), some identify as gender nonconforming (1%), and a couple opted to self-describe using their own terminology (0.5%). Our respondents span a range of ages, with each age category representing 10% or more of responses, but most (53%) are older than 51 years old (figure 1).

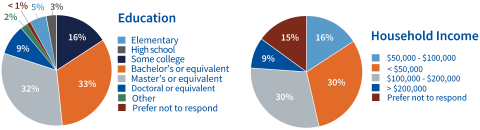

Most respondents (82%) selected white as their only race, have a higher education degree (74%), and have a household income less than $200,000 (76%) (figures 2 and 3). Respondents with a household income less than $50,000 are primarily 30 years old or younger (53%) or are 61–70 years old (23%). Most respondents (67%) live on the property year-round, while some live on the property part-time (11%) or do not live on the property at all (21%).

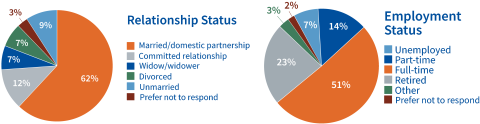

Most respondents (62%) are married (62%), while others are in a committed relationship (12%), widowed (7%), divorced (7%), or are unmarried (9%) (figure 4). Approximately half (51%) of respondents are employed full-time and approximately one quarter (23%) are retired (figure 5). Half of respondents (50%) have owned or managed the land for 10 years or less. Other respondents have owned or managed the land for 11–24 years (27%), 25–29 years (20%), and 50+ years (3%).

Reasons for Owning Land and Frequency of Recreational Activities

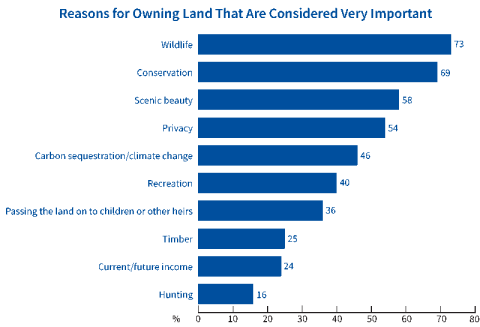

Respondents were asked to answer questions about the importance of owning or managing land and the frequency they participate in various recreational activities (figures 7 and 8). The five most important reasons women forestland owners and managers own and manage land in New Hampshire include:

- Wildlife (73%)

- Conservation (69%)

- Scenic beauty (58%)

- Privacy (54%)

- Carbon sequestration/climate change (46%)

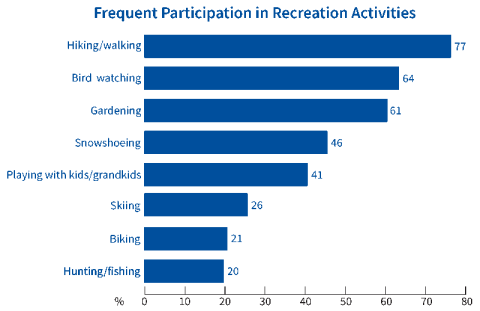

The five recreational activities that respondents participate in most frequently on the land include:

- Hiking/walking (77%)

- Bird watching (64%)

- Gardening (61%)

- Snowshoeing (46%)

- Playing with kids/grandkids (41%)

Additional activities mentioned include dog walking, camping, running, and photography.

Decision-making Characteristics

The survey asked respondents to answer questions about decision-making and goals for land management. The majority (66%) of those surveyed own land, while others (12%) manage land they do not own or have some combination of land ownership and management of land they do not own. Most landowners and managers (55%) make most management decisions individually, compared to having a group or family (including the respondent and their partner/spouse) (31%), or their partner or spouse alone (8%) act as the primary decision maker. Most respondents (63%) do not have conflicting goals and values with others who own or help manage the land. However, some respondents (17%) have conflicting goals and values with other decision-makers.

Overall, most respondents (65%) are satisfied with their decision-making arrangements for the property they own or manage. For respondents who are the primary decision maker, most (70%) think their decision-making works well, but some (17%) would like greater input from others (i.e., spouse, partner, family, co-owners).

For land that is managed by a partner or spouse, less than half (41%) of respondents feel that their decision-making works well. For land that is managed by a group or family, slightly more than half (52%) of respondents think their decision-making works well, but some (16%) do not feel heard or respected when they provide input to the group in charge of management. Additional comments include the desire for professional input and needing more guidance or education when it comes to making decisions about the land.

I am comfortable being the decision-maker, but I want to be educated enough to do it well

Planning for the Future

Respondents were asked to answer questions about their plans for the future of the land. Less than one-third of respondents (28%) plan to pass on land to heirs with instructions not to develop. Some respondents (21%) plan to prevent future development by placing a conservation easement or restriction on the land, while others (31%) have not decided or are unsure about their plans for the future, and several (5%) do have a goal of keeping land undeveloped in the future. Respondents were asked who would be the most likely to receive the land if it were sold or given away. Approximately half (47%) of respondents said the land would end up in the hands of their children.

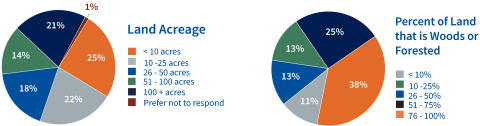

Forestland Characteristics

Respondents most commonly purchase land and often own or manage less than 25 acres. Slightly less than half (47%) of respondents own or manage less than 25 acres of land, and approximately one-third (35%) own or manage 51 acres or more (figure 9). More than half (60%) of respondents purchased their land and approximately one quarter (22%) inherited their land. Most respondents 71 years or older (78%) purchased the land and most 18–30 year olds (65%) inherited the land. More than one-third (38%) of respondents own or manage land that is 76–100% woods or forest (figure 10).

Generally, larger acreage properties have a higher percentage of woods or forest cover. Properties with 100 acres or more are mostly (69%) 76–100% woods or forest, and approximately one-third (36%) of properties that are less than 10 acres have less than 10% of woods or forest. One-third (33%) of respondents identified residential as the only use of the land, while others use the land solely for agriculture (10%), recreation (5%), timber production (5%), and commercial (3%) uses. Other responses include a variety of land use combinations.

I make the decisions but often do not have the knowledge or experience needed.

KEY TERMS

- Forest Stewardship Management Plan: A professionally written plan that outlines goals, objectives, and management activities for a property.

- Active Management: Involves habitat improvement for wildlife, timber harvesting, invasive species removal, or working with a professional forester.

- Passive Management: Infrequent management activities or changes on the property.

Management Activities

Women were asked to answer questions about forest stewardship plans and their management styles. Almost half (45%) of respondents do not have a forest stewardship management plan for the land, whereas almost half (44%) either have an up-to-date plan, revised their existing plan, or received a new plan. Approximately half (48%) of respondents actively manage the land. Most (54-55%) of respondents who are married or in a committed relationship actively manage the land. Less than one-third (31%) of unmarried respondents actively manage the land. When acreage size is compared to management style, most respondents (60%) who own or manage 100 acres or more actively manage the land (figure 11). Less than one-third (29%) of respondents who own or manage 10 acres or less actively manage the property (figure 11).

I think I know quite a bit about management, but most does not apply to me much because of the size of my land.

When age is compared to management style, respondents 31– 40 years old actively manage land the most (62%) and 18–30 year olds actively manage the least (30%) (figure 12). When income is compared to management style, respondents with larger household incomes are more likely to actively manage land, and household with lower incomes are less likely to actively manage land (figure 13). Most respondents (65%) with a household income greater than $200,000 actively manage land. Alternatively, most respondents (69%) with a household income less than $50,000 passively manage land.

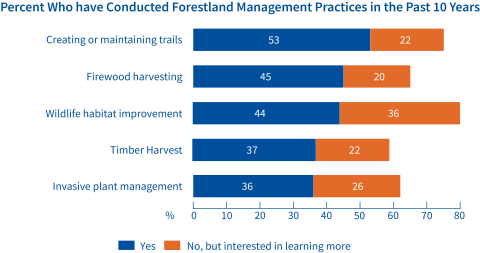

Women also answered questions about steps taken towards management (figure 14) and land management history in the past 10 years (figure 15). Approximately half (51%) of respondents have met with a forester. Many respondents have consulted state or federal professionals (46%) or have participated in a workshop related to forestry or wildlife habitat management (46%). In the past 10 years, approximately half (53%) of respondents have created or maintained trails on the property, and many respondents have harvested firewood (45%) or conducted wildlife habitat improvement projects (44%). Less than half of respondents are very likely (41%) or somewhat likely (38%) to complete a forestry or wildlife habitat management project on the property they own or manage. Approximately one-third (37%) of respondents who think conservation is a very important reason for owning or managing land have engaged with a conservation organization.

I feel we could be on the same page if everyone had the same information about how to manage the land.

Natural Resources Program Participation

Women also answered questions about their participation in a variety of natural resources programs (figure 16). The program respondents participate in the most (56%) is current use (a tax assessment program). Many have participated in conservation easements (28%), the Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) (24%), and the NH Tree Farm Program (21%). Few respondents have participated in New Hampshire Fish and Game's Small Grants Program (13%). However, many women are interested in learning more about all the programs; current use (21%), conservation easements (30%). NRCS EQIP (37%), NH Tree Farm Program (33%), and New Hampshire Fish and Game's Small Grants Program (37%).

Education and Learning

NATURAL RESOURCES KNOWLEDGE AND LEARNING STYLE

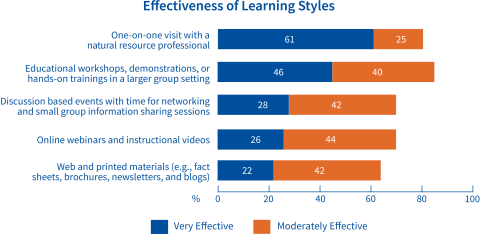

Women answered questions about their level of background knowledge and their preference for learning new information or skills. Less than half (45%) of respondents self reported they are moderately familiar with forestry and wildlife concepts; they have enough skills to implement some forestry and wildlife stewardship activities on their land. Many (36%) respondents self-report they are somewhat familiar with forestry and wildlife concepts. Some respondents (11%) self-report they are very familiar; they know as much about forestry and wildlife stewardship as most foresters or wildlife biologists. Others (8%) are not at all familiar with forestry and wildlife concepts. Most respondents (61%) find one-on-one visits with natural resource professionals to be a very effective method, and some (25%) find one-on-one visits to be a moderately effective method when learning new information or skills (figure 17). Respondents moderately (46%) or strongly (38%) agree that they are aware of resources available to help get them started in managing the land, and many moderately (42%) or strongly (35%) agree that they know how to access professional assistance and know how to contact contractors to help with projects. Many respondents moderately (40%) or strongly (26%) agree that they understand the laws and regulations pertaining to managing forestland in New Hampshire.

WORKSHOPS AND TOPICS

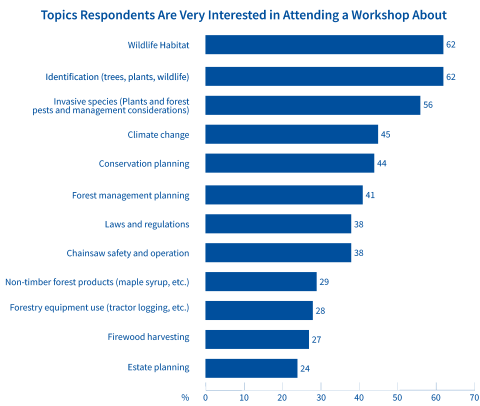

Approximately half (46%) of respondents have participated in a workshop related to forestry or wildlife habitat management. Many (26%) have not previously participated in a workshop related to forestry or wildlife habitat management, but are interested in learning more. More than half (61%) have participated in a UNH Extension workshop or program. The top five topics respondents are very interested in learning about are wildlife habitat (62%); identification (e.g., trees, plants, and wildlife) (62%); invasive species (e.g., plants, forest pests, and management considerations) (56%); climate change (45%); and conservation planning (44%) (figure 18). Respondents are also interested in learning more about a variety of topics and activities they have not previously participated in; less than one quarter are interested in meeting with a forester (23%); hiring a forester (23%); obtaining a conservation easement (23%); consulting a state or federal professional (22%); timber harvests (22%); trails (22%); firewood harvesting (20%); and hiring a logger (20%). Respondents are also interested in learning more about a variety of topics which include wildlife habitat improvement (36%); engagement with conservation organizations (26%); invasive plant management (26%); and speaking with a friend, neighbor, or family member about land management (14%).

Respondents are very likely to attend the the following types of workshops; partial-day (43%); weekend (34%); weekday (27%); full-day (24%); or evening (19%).

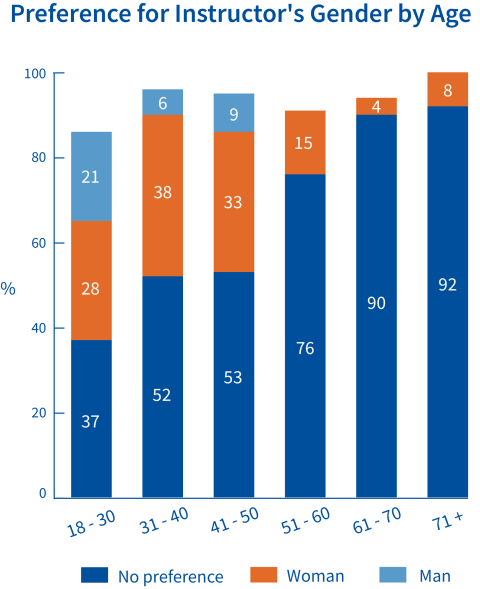

Respondents are somewhat likely to attend the the following types of workshops; weekday (36%); full-day (36%); partial-day (34%); evening (32%); or weekend (29%). Almost half (49%) of respondents are unlikely to attend overnight events. More than half (66%) of respondents do not have a gender preference for an instructor, while some (22%) prefer a woman instructor. Women who prefer a woman instructor are; 18–30 years old (28%); 31–40 years old (38%); 41–50 years (33%); 51–60 years old (15%); 61–70 years old (4%); and 70+ (8%) (figure 19). Women who prefer a male instructor are; 18–30 years old (21%); 31–40 years old (6%); 41–50 years (9%) (figure 19). Many respondents noted in the comments section that an instructor’s gender did not matter as much as their knowledge level and respect towards participants. Respondents are very likely (29%) or somewhat likely (21%) to attend women-only workshops, while others are neutral (41%), and some (9%) are unlikely to attend. Approximately one-third (35%) of respondents who are very likely to attend women-only events prefer a woman instructor. Additionally, some respondents (12%) who are very likely to attend women-only workshops are unlikely to attend mixed-gender events. Lastly, many respondents are very likely (25%) or somewhat likely (29%) to attend mixed-gender workshops, while others are neutral (38%) and some (8%) are unlikely to participate.

Information Sources

Women were asked about communication styles, social media, news sources, and trust. Respondents use email or text message often (54%) or almost always (24%) to communicate with friends and family. Additionally, respondents talk with friends or family either in person or by phone often (47%) or almost always (30%). Respondents almost always use the following social media sites: Facebook (19%); Twitter (12%); Instagram (12%); YouTube (9%); TikTok (9%); Snapchat (6%); and Reddit (5%). Respondents often use the following social media sites: Facebook (28%); YouTube (28%); Instagram (19%); TikTok (14%); Reddit (14%); Twitter (13%); and Snapchat (12%). Respondents almost always get news from: a mobile device (e.g., a smartphone or tablet) (35%); a desktop or laptop computer (32%); the radio (19%); local television (19%); national evening network television news (17%); newspapers in print (15%); cable television news (14%); and social networking sites (13%). Respondents consider the information they receive from the following sources to be very trustworthy; professionals or consultants (46%); national news organizations (34%); local news organizations (30%); friends, family, and acquaintances (16%); and social media (11%). More than half (54%) do not consider social media a trustworthy news source.

Barriers and Challenges

EDUCATION

Women answered questions about barriers that have prevented or discouraged them from attending educational workshops. Some reasons that have prevented or discouraged respondents from attending an educational workshop include distance from a training or workshop (70%); being too busy (64%); wrong time of day (60%); wrong topic (53%); a workshop being too technical (28%); lack of child care (27%); and not feeling comfortable (19%) (figure 20). Respondents also reported financial reasons as a barrier to participating in educational workshops. For respondents 41–50 years old, more than half (53%) of respondents said a lack of child care has prevented or discouraged them from attending an educational workshop (figure 21). For women 31–40 years old, slightly less than half (46%) of respondents cited lack of child care as a barrier.

My husband has passed. He was well aware of and very involved, because of his love for his heritage and this land, in working this large property. I never realized all that went into managing what I have as I worked off-farm to add to our income. I struggle financially to simply hold on to this property. I need to make some decisions and struggle to know where to begin.

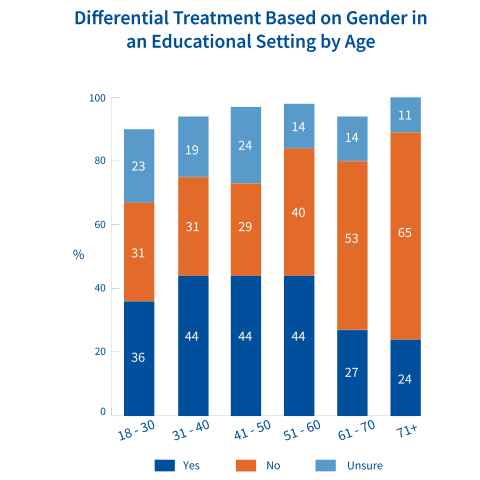

Many respondents who are somewhat (24%) or very interested (21%) in in attending workshops or trainings on forestry equipment have been discouraged or not attended an educational workshop due to not feeling comfortable. About half (52%) who are unlikely to attend mixed-gender events have been discouraged or not attended an educational workshop due to not feeling comfortable. Respondents reported experiencing differential treatment based on gender in professional settings (45%), personal settings (44%), and educational settings (35%). Slightly less than half (44%) of respondents in three different age categories (31–40 years old, 41–50 years old, and 51–60 years old) have experienced differential treatment in an educational setting (figure 22).

Sometimes I do not feel heard, as evidenced by being talked-over, my ideas not responded to or simply dismissed.

I have felt uncomfortable with most male foresters and have a hard time telling if they are giving me accurate and complete information. The one time I worked with a woman forester, it was fantastically and wonderfully different.

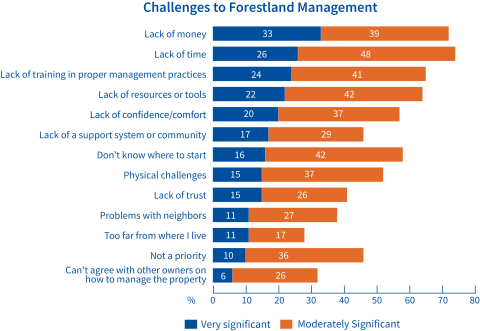

FORESTLAND MANAGEMENT

Women answered questions about challenges they face in forestland management. Respondents feel that their top five very significant challenges to forestland management are lack of money (33%), lack of time (26%), lack of training in proper management practices (24%), lack of resources or tools (22%), and lack of confidence/comfort (20%) (figure 23). Most respondents feel that the following are not significant challenges to owning and managing land; the land is too far from where they live (73%), cannot agree with other owners about how to manage the land (68%), problems with neighbors (62%), lack of trust (59%), and lack of a support system or community (54%). Most respondents (68%) who are not aware of resources available to help them get started with forestland management passively manage the land they own or manage.

There is a general sense that in some areas (including forestry) women are less capable, less knowledgeable, less physically able to do the work.

There truly is not a week that goes by where I haven’t observed some differential treatment that is obviously based on my gender as a woman.

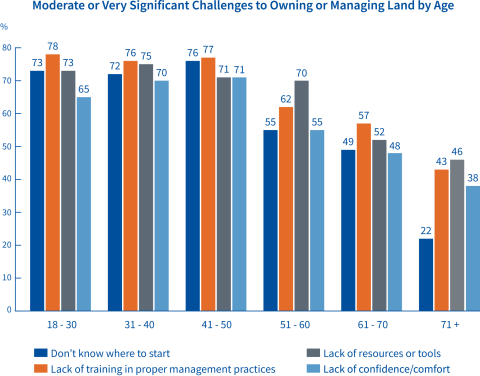

The biggest challenge for forestland owners and managers 18–50 years old is lack of training in proper management practices (figure 24). For most respondents 18–60 years old, the following reasons are moderate or very significant challenges to owning or managing land.

- Lack of confidence/comfort: 18–30 years old (65%); 31–40 years old (70%); 41–50 years (71%); and 51–60 years old (55%) (figure 24).

- Do not know where to start: 18–30 years old (73%); 31–40 years old (72%); 41–50 years (76%); and 51–60 years old (55%) (figure 24).

I do not understand the economic side of forestry management and as such I have no way to gauge if a potential contractor is making a fair and honest assessment of the expense to conduct work on the property.

For most respondents 18–70 years old, the following reasons are moderate or very significant challenges to owning or managing land.

- Lack of training in proper management practices: 31–40 years old (76%); 41–50 years (77%); 51–60 years old (62%); and 61–70 years old (57%) (figure 24).

- Lack of resources or tools: 18–30 years old (73%); 31–40 years old (75%); 41–50 years (71%); 51–60 years old (70%); and 61–70 years old (52%) (figure 24).

- Lack of time: 18–30 years old (75%); 31–40 years old (82%); 41–50 years (89%); 51–60 years old (86%); and 61–70 years old (56%) (figure 25).

- Lack of money: 18–30 years old (65%); 31–40 years old (89%); 41–50 years (83%); 51–60 years old (84%); and 61–70 years old (63%) (figure 25).

I am an Asian woman in my 50’s. When dealing with local contractors (logger, plumber, electrician, chimney sweep) the business transaction is VERY different than when my Caucasian husband negotiates the work, timing, and cost.

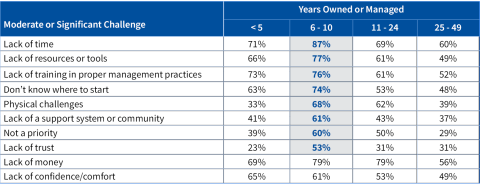

For most respondents 18–60 and 71+ years old, physical difficulties are a moderate or very significant challenge to owning or managing land. They are; 18–30 years old (56%); 31–40 years old (60%); 41–50 years (54%); 51–60 years old (53%); and 71+ (73%) (figure 25). Forestland owners and managers 71+ years old have the highest proportion of physical challenges. For most respondents 18–40 years old, a lack of support system or community is a moderate or very significant challenge to owning or managing land for those who are; 18–30 years old (61%); and 31–40 years old (58%) (figure 25). We also examined challenges in relation to how many years respondents have been responsible for the land to see if newer landowners and managers (<10 years) faced unique challenges. Generally, it appears that newer landowners face similar moderate or very significant challenges to those with longer tenures (11+ years) which include; lack of time, lack of resources or tools, lack of training in proper management practices, not knowing where to start, lack of money, and lack of confidence/comfort. However, respondents who have owned or managed land for 6–10 years have the highest proportion of moderate or significant challenges in 8 out of the 10 categories surveyed (table 1).

I definitely frequently feel mistreated and mistrusted by foresters or especially loggers because I am a woman. The assumption is that I do not know anything about the land I’m managing or about the forestry practices that are being conducted and discussed.

Scheduling can be challenging if only one workshop session is offered, especially if it is only publicized close to the date. I work from home, have generous flex/vacation time, and no children's activities to consider, and yet it has still happened that the only session of something I wanted to attend falls on a day or time that I have commitments that cannot be rescheduled. Publicizing in advance helps people to plan around your workshop, or offering multiple sessions for flexibility, would increase access.

Conclusions

Demographics, Behaviors, and Management Barriers

Our results show that women in New Hampshire who own or manage land manage do so with a variety of goals, most frequently including wildlife, conservation, and scenic beauty. These reasons align with the types of recreation women landowners and managers participate in the most frequently which include hiking or walking, bird watching, and gardening. Most respondents are married, live on the property year-round, and do not have conflicting goals and values with others who own or help manage the land. A large portion of respondents have owned or managed the land for less than 10 years and would likely benefit from outreach strategies targeted at women with less forest management experience to help them achieve their goals.

Almost half of respondents do not have a forest stewardship management plan, despite a large majority being somewhat or very likely to complete a forestry or wildlife habitat management project and being somewhat or very likely to hire a natural resource professional. Additionally, many respondents have enough skills to implement some forestry and wildlife stewardship activities on the land. However, almost half of respondents are not actively managing the land they own or manage. This lower participation in management activities and engagement with natural resources professionals is likely due to a variety of moderate or significant challenges which include lack of time, lack of money, lack of training in proper management practices, lack of resources or tools, and not knowing where to start. It is apparent then, that education is needed about the importance of forest management activities and how those projects can help women achieve their goals for the land they own or manage.

Workshops and Trainings

Focusing workshops or training topics on wildlife habitat, identification (e.g., trees, plants, wildlife), invasive species (e.g., plants and forest pests and management considerations), climate change, and conservation planning may lead to an increase in participation from women forestland owners and managers. Facebook is the most often used social media site and can be an effective way to communicate upcoming workshops and trainings to the public. The most common reasons that prevent respondents from attending educational workshops include distance from the event, being too busy, wrong time of day, too technical, and lack of child care. If targeting specific age demographics, there may be an increase in participation from respondents 31–50 years old if child care is provided at workshops. Slightly more respondents are very likely to attend workshops or trainings on weekends compared to weekdays. Partial-day events are more likely to be attended, but many respondents are somewhat likely to attend full-day events. Based on these results, partial-day workshops and trainings repeated at different locations around the state on weekends may be better attended.

I have a mixed feeling of providing input, and not feeling heard. Sometimes I wonder if this frustration stems from desiring a greater role, but not really feeling sure how I could be doing what I am doing differently.

Learning Environment

When learning new information or skills, most respondents find one-on-one visits with natural resource professionals to be the most effective, followed by educational workshops, demonstrations, or hands-on training in a larger group setting. Approximately one-third of respondents have experienced differential treatment based on gender in an educational setting and most respondents do not have a gender preference for an educational instructor. There was no significant difference between preference for women-only events or mixed-gender events. Because half of respondents surveyed are very likely or somewhat likely to attend women-only workshops, it may be beneficial to offer more opportunities for women-only events to provide a more comfortable environment for those less-likely to attend mixed-gender events. These results highlight opportunities to engage newer or less active landowners and provide them with forestry and wildlife habitat management educational opportunities, tools, and resources.

Natural Resources Program Participation

Based on our findings, it is clear that many women are interested in learning more about natural resources programs. Respondents said that a lack of money

was the most significant challenge to forestland management. With that in mind, natural resources programs provide a valuable opportunity to help women landowners and managers in New Hampshire achieve their management goals. More thoughtful education and outreach efforts about these programs may increase participation and result in more projects on women-managed forestland.

Final Thoughts

Based on our results, there is a need to provide education programs targeted to women forestland owners and managers. Women-focused programming should be designed with a comfortable environment in mind, paying close attention to convenient times of day, learning styles, and topics of interest. The information collected from this survey will inform strategies for women-focused program development, workshop topics, resource creation, and technical assistance. Future studies might consider how men and women differ in their beliefs, barriers, challenges, characteristics, and experiences.

RESOURCES

Forest Management

- Women in the Woods

- UNH Extension County Foresters

- UNH Extension Forestry

- Good Forestry in the Granite State

- New Hampshire Forest Action Plan (2020)

- Landowner Goals and Objectives Worksheet

- Mapping Your Property

Wildlife

- UNH Extension Wildlife

- New Hampshire Fish and Game

- New Hampshire Wildlife Action Plan

- Taking Action for Wildlife

- Focus on Wildlife Brochures

- Habitat Stewardship Brochures

Conservation

Natural Resources Programs

- New Hampshire Fish and Game's Small Grants Program

- Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) - The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP)

- New Hampshire Tree Farm Program

- Current Use (Tax Assessment)

REFERENCES

- Butler, S. M., Huff, E. S., Snyder, S. A., Butler, B. J., & Tyrrell, M. (2017). The Role of Gender in Management Behaviors on Family Forest Lands in the United States. Journal of Forestry. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.2016-076R2

- Redmore, L. E., & Tynon, J. F. (2011). Women Owning Woodlands: Understanding Women’s Roles in Forest Ownership and Management. Journal of Forestry, 109 (5): 255–259.

- Butler, B. J., Hewes, J. H., Dickinson, B. J., Andrejczyk, K., Butler, S. M., & Markowski-Lindsay, M. (2016). USDA Forest Service National Woodland Owner Survey: National, regional, and state statistics for family forest and woodland ownerships with 10+ acres, 2011-2013 (NRS-RB-99; p. NRS-RB-99). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. https://doi.org/10.2737/NRS-RB-993

- Butler, B. J., Hewes, J. H., Dickinson, B. J., Andrejczyk, K., Butler, S. M., & Markowski-Lindsay, M. (2016). Family Forest Ownerships of the United States, 2013: Findings from the USDA Forest Service’s National Woodland Owner Survey. Journal of Forestry, 114(6), 638–647. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.15-099

- Warren, S. T. (2003). One Step Further: Women’s Access to and Control Over Farm and Forest Resources in the U.S. South. 19, 21.

- McGrath, F. L., Smalligan, M., Watkins, C., & Agrawal, A. (2021). Exploring Environmental Attitudes and Forest Program Uptake with Nonindustrial Private Forest Owners in Michigan. Society & Natural Resources, 34(4), 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2020.1833122

- Markowski-Lindsay, M., Catanzaro, P., Zimmerer, R., Kittredge, D., Markowitz, E., & Chapman, D. A. (2020). Northeastern Family Forest Owner Gender Differences in Land-Based Estate Planning and the Role of Self-Efficacy. Journal of Forestry, 118(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/jofore/fvz058

- Pröbstl-Haider, U., Mostegl, N. M., & Haider, W. (2020). Small-scale private forest ownership: Understanding female and male forest owners’ climate change adaptation behaviour. Forest Policy and Economics, 112, 102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102111

- Fegel, T., McGill, D. W., Gazal, K. A., & Smaldone, D. (2018). Educational Preferences of West Virginia's Female Woodland Owners. Journal of Extension, 56(1), Article 10. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol56/iss1/10

- Miner, J., Dwivedi, P., Izlar, R., Atkins, D., & Kadam, P. (2021). Perspectives of four stakeholder groups about the participation of female forest landowners in forest management in Georgia, United States. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0256654. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256654

- Harriman, H. C., Fuhrman, N. E., Kelsey, K. D., & Woosnam, K. M. (2020). Forestland management and empowerment: A phenomenological inquiry into the experiences of women forestland managers in the state of Georgia, USA. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 1(2), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v1i2.43

Women in the Woods Team

- Haley Andreozzi, UNH Extension State Specialist, Wildlife Conservation

- Amy Gaudreau, UNH Extension Forest Stewardship Outreach Program Manager

- Wendy Scribner, UNH Extension Natural Resources Field Specialist

- Cheri Birch, New Hampshire Timberland Owners Association Program Director

- Wendy Weisiger, Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests Managing Forester

The University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension is an equal opportunity educator and employer. University of New Hampshire, U.S. Department of Agriculture and N.H. counties cooperating.

Are you interested in learning more about Women in the Woods and upcoming events?

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates.