The Art and Science of Forestry in The Granite State

The term forestry is often defined as the art and science of growing and managing forests. That certainly has a nice ring to it, but what exactly do we mean by art and science and what role does each play when managing forests?

The Science of Forestry

Good forestry is grounded in good science. In other words, sound forest management decisions and practices are guided by the most current and established science. In general, science of forestry refers to the systematic study of natural and human factors that affect, or are affected by, forest ecosystems. The purpose of scientific research is to use observation and experimentation to generate data that, when analyzed and interpreted, generate new knowledge, verify existing theories, or attempt to answer specific research questions.

Forestry draws on a range of scientific disciplines. Fundamental research in ecology, wildlife biology, hydrology, and tree/plant physiology have yielded a foundation for understanding forest ecosystem dynamics. In addition, knowledge generated from the social sciences (sociology, economics, etc.) help foresters and natural resource professionals better understand human attitudes, values, and behaviors related to forests, which in turn informs policy and management decisions. Moreover, contributions from disciplines such as remote sensing, tree genetics, climate science, and biomaterials, will continue to inform critically important issues, including forest health, climate change, and the development of bio-based products that can reduce our dependency on more malignant materials.

Forest Science in the Granite State

New Hampshire has a long history of forest science and research. The Granite State is home to two experimental forests, the Bartlett Experimental Forest and the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, both located within the White Mountains National Forest and managed through the US Forest Service’s Northern Research Station. These two forests have been sites of scientific research since 1931 and 1955, respectively.

Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest sign.

Research on the Bartlett Experimental Forest has made important contributions to our understanding of northern hardwood forests, their development, and their response to management. That body of research directly informed the development of the Silvicultural Guide for Northern Hardwoods in the Northeast, which continues to guide foresters and landowners throughout the range of the northern hardwood forest type. More recently, the Bartlett has supported a range of research projects focusing on wildlife habitat as well as application of remote sensing technologies.

Research conducted at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest has broadened our understanding of forest ecology and hydrology. Of note, the site is home to a watershed-scale experiment conducted in the 1950s and 1960s that examined the effects of timber harvesting and air pollution on water yield and stream chemistry. That work directly contributed to the passage of the Clean Air Act Amendments and has shed light on the importance of protecting headwater streams and the use of maintaining riparian buffers to mitigate nutrient leaching during and following a timber harvest.

In addition to these experimental forests, researchers at the University of New Hampshire, and other research institutions throughout the region, continue to conduct forest research on a host of critically important issues. The results from these and future studies will continue to inform management and policy decisions now and into the future.

Student using radio telemetry equipment. Photo credit: University of New Hampshire.

The Art of Forestry

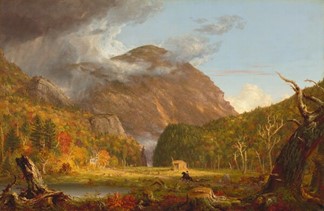

The phrase - art of forestry - may conjure images of famous landscape paintings by Thomas Cole or his contemporaries who were inspired by the White Mountains. And while a well-managed forest can be a thing of beauty (aesthetics is a common management objective), the art of forestry refers to the decision-making processes that foresters and landowners go through to determine a course of action. In short, the art is what my silviculture professor, Dr. Ralph Nyland, referred to as “what happens between your ears.”

In essence, a forester must apply their knowledge to develop management prescriptions that are well-suited to a given site and forest condition and that have a high probability of achieving the desired outcome based on landowner objectives.

A View of the Mountain Pass Called the Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch) by Thomas Cole

Easy enough, right? Well, there are numerous complicating factors. For example, in New Hampshire, we have a variety of forest types that may call for different management strategies based on the unique characteristics of the tree species, soils, and terrain. A forester also may be working in degraded stands that have a history of exploitative cutting or poor land management, leaving few opportunities for management. Furthermore, landowners often have multiple objectives that may or may not conflict with each other, which require foresters to weigh the trade-offs between various management options.

Foresters also must consider the possibility of future events that can impact outcomes, such as risk of natural disturbances (pest outbreak, ice storms, fire, major wind event, etc.), as well as the economic feasibility of any management recommendations. If planning a timber harvest or other forest operation, the forester must also consider the timing of the operation and the type of equipment best suited for the job. All this while also while anticipate effects of climate change and invasive species over long-time horizons, and while keeping track of local markets, new technologies, and the latest science.

At a smaller scale, it’s the forester’s use of a paint gun that ultimately determines the fate and future trajectory of a stand. When marking a stand for harvest, foresters make hundreds of decisions about which trees to cut and which trees to leave to grow. Those decisions are based on a variety of factors, including:

- tree species

- tree form and health

- potential wildlife benefits (cavities, mast, structure, etc..)

- target spacing and stand density

- position in the canopy

- proximity to water resources or protected sites

- accessibility by logging equipment

In short, the process of forest management planning and decision-making is complicated. Decisions occur at various scales and must consider multiple factors. Scientific research is critically important in the development of fundamental knowledge, as well as practical guidelines and tools (e.g. stocking charts, site index curves, growth models, etc.). The art is the ability to integrate that knowledge and apply various tools to determine management activities that have a high likelihood of satisfying landowner objectives.

When done well, and based on the best available science, the practice of forestry is truly an artform.

Have a question about your woods? Contact your Extension County Forester today!

Do you love learning about stuff like this? Subscribe to the NH Woods & Wildlife Newsletter.

A quarterly newsletter providing private woodlot owners in New Hampshire with woodlot management news, pest updates, resources, and more.