A Few Tree Pruning Basics

With the January thaw my husband and I had an opportunity to get a good start on the annual winter chore of pruning our small apple orchard. Pruning creates wounds that can provide an entry for pests and diseases, so is best done during the dormant season. Also, this is when the trees are bare and the branches are easier to see.

Our concept of small began with the choice of trees for our suburban lot. We planted dwarf and semi-dwarf trees when we moved here in the 80s. My father was an apple-grower with a farm on the shores of Lake Ontario in western NY. We did not live on the farm, but were ushered there to work packing apples on Saturdays in the fall, or to swim in the lake in the summer. We drove down the lane through the orchards to get to the lake, so I have a clear memory of what a standard sized apple orchard looks like. Of course, I was a little girl and the trees looked huge to me.

This mature orchard was planted in 1860 before dwarf trees were available, so the trees were standard size that grow tall and big. They were severely pruned to manage for apple production, thinned to permit maximum sun on the fruit, and topped for easier spraying and picking. They were spaced so the teams of horses in the early days, and later tractors pulling the spray rigs, could drive between the rows. Also, the trailer with a high pruning platform could be pulled along beside the trees.

Our dwarf tree idea was short-lived. They somehow got bigger than expected. We now have an orchard jungle leading to many serious discussions about how to prune. This is because we each have different goals or reasons to prune in mind. Ted wants quantity while I am looking for quality, which requires space for the apples to grow in the sun to get big and red. Space between branches also permits good air flow so the apples dry, which helps control fungal diseases. Ted is more concerned about the deer that too often get under or over the 8-foot fence and eat the buds in early spring. He wants to leave the straggly long low branches to protect the rest of the tree. A network of intersecting tree branches helps to keep deer away from the center of the orchard but makes mowing miserable. We both agree that we can’t let the trees get too tall, because we can’t prune, spray or pick the apples high over our heads.

Pruning trees for fruit production is far different from pruning and shaping trees and shrubs in the landscape for aesthetic or other reasons. Limbing up trees can open up a view under the high canopy or encourage the upright growth of a central leader. Other pruning goals are explained in a concise and comprehensive UNH pruning fact sheet: “maintaining plant vigor, creating and preserving good structure, increasing fruit and flower production, improving health, enhancing ornamental characteristics, and limiting plant size.”

https://extension.unh.edu/resource/basics-pruning-trees-and-shrubs-fact-sheet

Some basic pruning techniques are the same no matter what the goal; they are dictated by plant biology based on how woody plants grow. Different from animals, plants don’t heal wounds, but wall off damaged areas by creating a barrier around the injury site.

Dr. Alex Shigo, (1930 – 2006) chief scientist for the US Forest Service, examined trees from the inside out to figure out how they grow. This understanding provided clues and guidance to how to prune them with minimum damage by making clean, neat cuts next to the branch collar so the wound will heal quickly. His research revolutionized the existing standard pruning practices:

Early in his career, the first one-man chainsaws became available. These enabled him to prepare longitudinal sections of trees, which allowed him to study the longitudinal spread of decay organisms within them. A major discovery from this work was that trees have ways of walling off decaying tissues, which he named Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees (CODIT). This led to reassessment of arboricultural practices such as pruning techniques and cavity treatments, which showed that many then current practices (such as coating cuts with tar) actually promoted decay or were ineffective. The ANSI A-300 Pruning Standard reflects his recommendations.

Dr. Shigo, who retired to Durham in 1985, presented a program about tree pruning and care that then Tree Stewards (now Natural Resources Stewards) were invited to attend. I was enthralled with his explanation of how the annual tree growth rings overlap at the branch attachments. This forms a very strong branch connection capable of withstanding high winds and heavy ice and snow. Stacking firewood became more interesting as I discovered examples in split logs with branch attachments that showed the layers of tree rings at the base of branches.

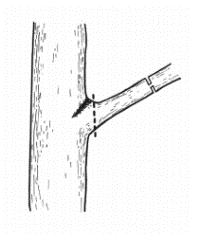

The dense area of cells in the collar are able to grow over the branch stub quickly, especially if it is not torn when the branch is removed. Make pruning cuts close to the collar, perpendicular to the branch. You can see why long stubs are bad - it takes more years for the tree to grow wood over them. Collars differ on various species, and some trees don’t have them. Look for a bulge at the base of the branch.

Large Branch Removal: Avoid tearing bark by making an undercut on the lower side of the branch, before making a second cut directly above the first.

https://extension.unh.edu/resource/pruning-deciduous-trees

Trees try to cover wounds when they grow the new spring layer of wood. Around huge wounds it forms a curled growth at the edges of the scar as shown in this chunk of firewood. The curls can get so big before they meet in the middle of a large scar that they can split the tree trunk.

I saved this tree hole from the wood pile and finally know why; it shows the inside of a tree branch collar and the build-up of the new wood that year-by-year shrinks the size of the hole. Look for the other black ring around the hole on the inside.

My other winter pruning task was to limb up my 4-year-old butternut tree sprout that I grew from a nut. I planted it in the ground three years ago on the west side the house for shade. It doubled in size last summer

All the branches are just one year old. Since I want a tall tree with a high canopy, I knew I needed to prune off all the year old branches, except for one leader. Courageously, I cut off all but three of them in late fall and in January I cut off two more leaving the straightest one for the leader. Since the shoots grew from buds on the prior year’s leader tip, they were bunched close together. I didn’t want to girdle the tree by cutting them all off at once.

Now I have a perfect example to show the cluster of branch collars with the branch stubs that will quickly be healed over by the growth from the collar. I expect to continue to do this for a few years so that I will eventually have a tall, blemish free trunk.

For specific pruning instructions, there are many good fact sheets at university sites:

Iowa - timing - https://hortnews.extension.iastate.edu/2014/02-14/pruning.html

Colorado detail - drawings - https://static.colostate.edu/client-files/csfs/pdfs/613.pdf

Vt Forestry - one page fact sheet tree - https://fpr.vermont.gov/sites/fpr/files/Forest_and_Forestry/Community_Forests_and_Trees/Library/Pruning_Trees.pdf

Related Resource(s)